Haven't we all grown up reading and listening to fantastical stories of dragons and dungeons, witches and beasts, princes and beauties? Of course, fairytales have enchanted us all! They are miraculous and beautiful, and their potency lies in them being mystified. Fairytales are but a historical prescription, intended to allay young minds of fear and condition them to know the ways of their society. They are also strong indicators of the level of civilisation, of the essential quality of a culture. So what happens when these tales are subverted to question the exact same notions they were invented to preserve?

The feminist artist who goes by the name of her alter-ego Princess Pea, drawn from Hans Christian Andersen's fairytale of the Princess and the Pea, presents her first solo exhibit in the city titled Pecked, Jostled and Teased. Constantly mocked for her petite frame while growing up, the young artist introspected on the physical attributes that society sanctioned and deemed 'beautiful'. Who could be a little princess and what did it take for all little girls to be like her? With the plethora of fashion magazines and beauty paraphernalia feeding our understanding of womanhood, Princess Pea attempts to expose the hypocrisy of the gender bias.

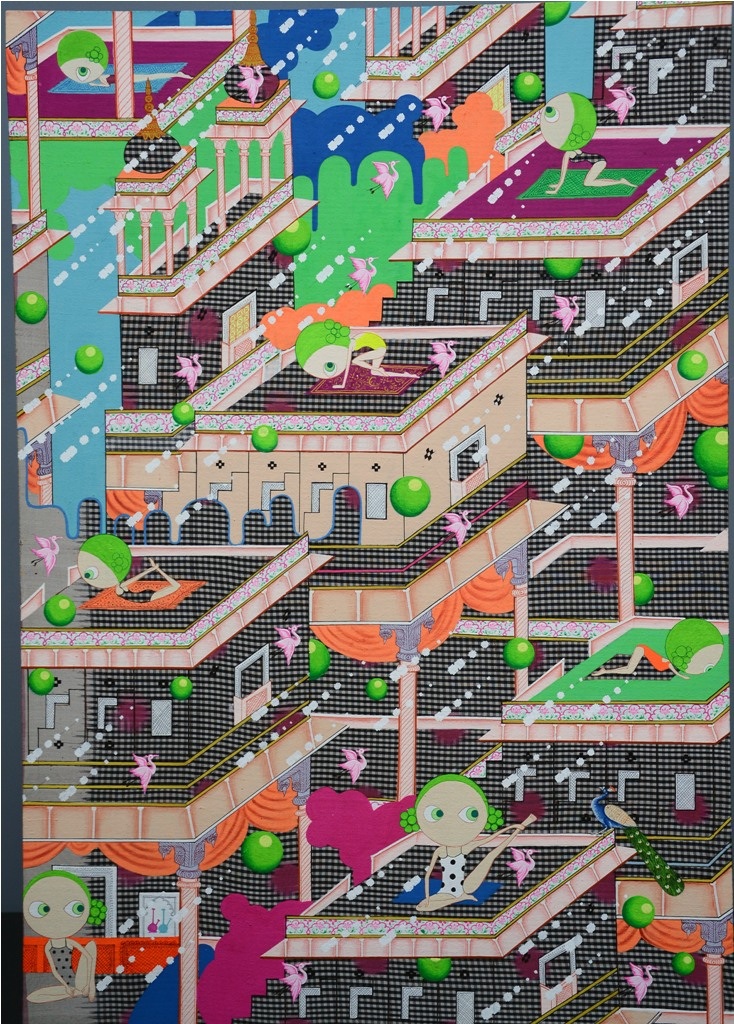

Princess Pea is in her early 30s, is of a small frame, and adorns a giant anime inspired head as her own. The head with green pea-like bobbles on either side has become a trademark of her identity, and of a seemingly carefree absurdity. All her work is autobiographical, presented as pop art, making the intended satire even more hard-hitting. Her recent show includes a striking series of mixed media paintings — a compositional fusion of Indian and Mughal miniatures with computer generated video games. There is a detailed logic in her use of each motif — a palace with groomed gardens and many peacocks, a royal prince gazing from a balcony; the balcony contrived as another level for the gamer to clear and by extension, another standard to aspire to. I look closer to find Stan and Kenny from the sitcom South Park in a battle scene, as a reference to the dark humour they stand for, and an insight into her lived reality. The green bobbles emerge again, like amorphous blobs, that converge to form the top of a tree or fragments of a meteoric shower, commanded by Princess Pea to destroy all forms of patriarchy that assign the woman a place of second gender.

A wall mounted with seven found stuffed toys represents the once friends and pets of the children who owned them; each with an oversized faceless head, each discarded after the fallacy of their companionship was realised. Alongside is a series of eight wooden dolls, allegedly modeled along Princess Pea's physical type, displayed inside glass cylinders as specimens of strong personalities taken from mythology and reality — Draupadi, Marjane Satrapi, The Red Queen, Mary Kom, Yoko Ono, Anya, Barbara Thornson and Ottoline. Their projected identities are representations of strength and respect, for which each is revered and admired. In doing so, the artist insinuates the erroneous generalisation of man being the superior gender.

Princess Pea's angst is most felt in the honeycomb shaped room that is sound proofed and fitted with three cameras. The interactive piece urges women to go in and scream, derived from the logic of "making their voices heard". The recording from inside the room is viewed by the Princess in a cordoned-off room of the gallery, where she sits with her enormous white head, dressed in a lacey vintage gown watching quietly. The piece is ambitious to say the least, but in line with an earlier project wherein roles are reversed and she sits in front of the cameras inside the same portable room while others view her activities from the outside.

Princess Pea successfully makes real the fantastical, and in its strange silliness she ridicules the society we live in and its concocted notions of beauty. Yet, she still feels the need to mask her identity as an artist behind anonymity and maintains only her alter-ego persona of Princess Pea in the public domain.