A photograph tells a story. In fact, it can tell many. The story depends on the temperament of the subject and its context, whether it is a historical document or an image that was contrived or staged. With the barrage of images used for propaganda, manipulated or not, it is difficult to know the difference. Eager to learn more about journalistic photography and its many nuances, I sought out Delhi-based freelance photographer Sumit Dayal, whose images have been featured in magazines like TIME andNational Geographic. How authentic, I asked him, is the image to the story and how does it align with an artist's personal vision?

Sumit Dayal was born in Kashmir and brought up in Nepal, and has focused his work on South Asia and the cultural identities that these regions protract and eschew. Over coffee on an early Monday morning, we discussed his recent visit to New York and the progressive impact that social media has on the future of photography as a documentary medium. The popularity of the smartphone and applications that allow anyone to publish their photographs in three easy steps has made everyone an author. However the speed with which these are uploaded, and the multiplicity of sources, makes the idea of authorship redundant. Having said this, there is a credibility that, say, TIME has built over many years. But how does a magazine cope with the decreasing relevance of print? And how do we react to the changing interface? "Everyone simply adapts," he explains.

As Dayal travels and camps all over the world, he excavates and documents the psyche of the land as he experiences it, without a prior agenda.

Dayal discovered his interest in photography quite by accident, after a chance apprenticeship with renowned photo-activist Thomas Kelly in Nepal. On his advice, Dayal went on to graduate with a degree in documentary and photo journalism at the International Center of Photography in New York in 2006. With a keen appetite for the thrills of photojournalism, he headed to one of the most dangerous and sensationalised regions of the time — Afghanistan, to cover the war's impact on local populations. The resulting series, titled "Afghanistan, No Strings Attached, 2007" is a compilation of everyday scenes that belie the precision of the camera, for they reflect a reality that is blurry, rough on the edges and often surreal.

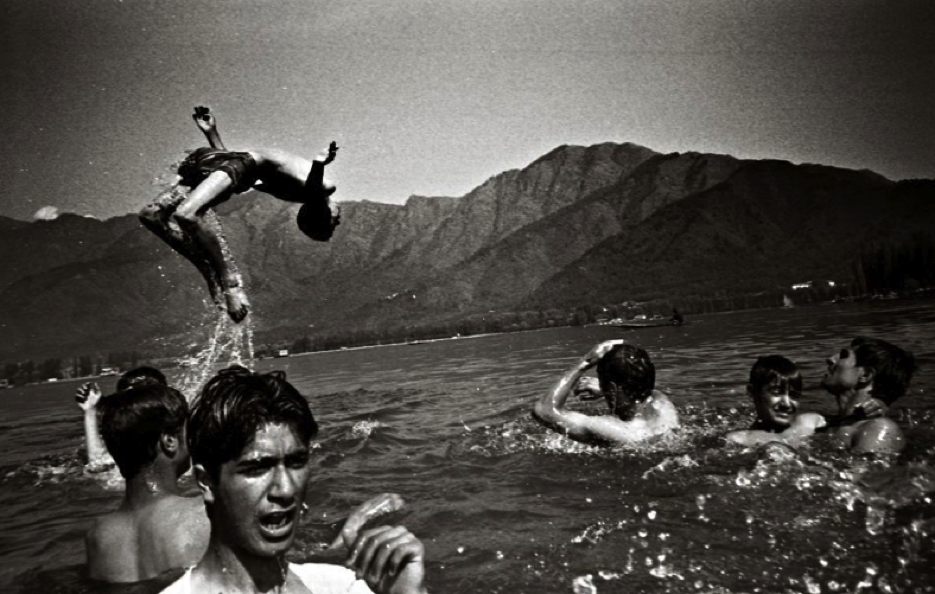

Dayal has since photographed the marginal and immigrant peoples of India, Nepal, Bangladesh and Bhutan. But it is his work on Kashmir, personal and ethnographically researched, that won him National Geographic's All Roads Photography Program in 2010. The continuing series, "On Going Home", sketches a personal timeline of observations along the Line of Control, all the way from Punjab to Ladakh. As he travels and camps, he excavates and documents the psyche of the land as he experiences it, without a prior agenda. He explains his inclination toward portraiture as a way to detract from the banality and blandness of the landscape, consequently accenting a specific emotion that is focused within the frame of the composition. Begun in 2009, Dayal's work in Kashmir is ongoing, and has the potential of remaining a historical record of our times.

As we come full circle to where our conversation began, Dayal informs me of his latest initiative called The India Photo Project, formed on the mobile photo-sharing platform Instagram. Fed by submissions from select Indian photographers, the collective aims to record the visual evolution of life and living in the world's largest democracy, wherein each image documents and relays strong voices in a manner that is both unbiased and free. As a new follower, I too am fed a daily dose of stunning and poignant images, along with many others, that still raise the question of how true the photograph is to the reality it attempts to capture.