How galleries, intellectuals, and patrons have shaped contemporary Indian art

India is a country rich with history, and its heady mix of colors and sounds, tastes and appetites, positions and compositions are embedded in the country’s cultural landscape. But despite the plethora of diverse artistic practices, a new generation of forward-thinking curators, and platforms with an international reach, such as India Art Fair, Kochi-Muziris Biennale, and Serendipity Arts Festival, the contemporary art ecosystem in India is largely still overlooked by the state. Adequate infrastructure to support public institutions and artists through funding opportunities like grants and awards has not appeared. Consequently, a handful of patrons-turned-gallerists have expanded their roles beyond their conventional scope and become the bedrock of the contemporary Indian art scene.

Left: Krishen Khanna, Who is it?, n.d. Right: N.S. Bendre, Untitled (Mother and Child), n.d. Khanna was a Mumbai’s Progressive Artists Group, while Bendre was part of the Baroda group. Both works were presented by DAG Gallery at Art Basel Hong Kong 2015.

Amid the spirited inception of ideologies and practices at some of the most prominent art schools of the 20th century – for example, Kala Bhavan in Santiniketan, Maharaja Sayajirao University in Baroda, Sir J.J. School of Art in Mumbai, and Delhi College of Art – friendships grew between artists and patrons, many of whom established commercial galleries that still exist today. These include Kumar Gallery (est. 1955, New Delhi), Chemould Prescott Road (est. 1963, Mumbai), Pundole Art Gallery (est. 1963, Mumbai), Art Heritage (est. 1977, New Delhi), Vadehra Art Gallery (est. 1987, New Delhi), and Gallery Espace (est. 1989, New Delhi), which was opened by the industrialist Renu Modi on the advice of Modernist artist M.F. Husain. Functioning as both the establishment and market, these galleries reflect the interwoven fabric of commerce, patronage, and pedagogy that have evolved in the cities of New Delhi, Mumbai, and Kolkata.

Building an art infrastructure out of a vacuum, and doing so without a formal art education, the early players straddled art production and business, shaping the scene through passion more than skill, with guidance from friends and artists. Today, these establishment figures offer a broad cross-section of Modern and contemporary Indian art, as the next generation leads the galleries into new ventures and formats that better serve the country’s artistic capacity. Vadehra’s artists, for instance, reflect the transition from Modern to contemporary, representing Modern Masters such as Benode Behari Mukherjee and V.S. Gaitonde, pioneering artist-educators including Rameshwar Broota and Gulammohammed Sheikh, and contemporary luminaries such as Nalini Malani and Shilpa Gupta. In 2007, the gallery launched the not-for-profit Foundation for Indian Contemporary Art, stewarded by Roshini and Parul Vadehra, respectively the daughter and daughter-in-law of the gallery’s founder, with key figures from the artworld, including Hans Ulrich Obrist and Ranjit Hoskote, on its advisory board.

Formerly a framing studio, Chemould Prescott Road, whose artists include Gupta, Anju Dodiya, and Rashid Rana, continues to respond to the sociopolitical climate, having served as a shelter and watering hole for artists amid the Mumbai riots of the early 1990s. At the time, recalls the gallery’s owner and director Shireen Gandhy, it began to support artists with projects that were unremunerative and experimental for the time. These included Malani’s City of Desires (1992), which converted the entire gallery into a site-specific installation that involved covering the floor with terracotta powder. ‘Such projects needed to have institutional support,’ Gandhy says. ‘Even if it was momentous and spontaneous to some extent, we were very aware that the gallery was really taking the place of a museum.’

Installation view of Nalani Malani's exhibition Casandra's Gift, Vadehra Art Gallery, 2014. Courtesy of Vadhera Art Gallery, New Delhi.

A notable, later addition to India’s gallery scene was Nature Morte, cofounded originally in New York’s East Village in 1982 by Peter Nagy, who rode a wave of global interest in Indian contemporary art by the likes of Bharti Kherand Dayanita Singh. Opened in New Delhi in 1997, the gallery became a respected fixture in the city, representing recognized names and younger artists such as Seher Shah, Tanya Goel, and Asim Waqif. Comparing the scenes in New York and New Delhi, Nagy says, ‘We desperately need more commercial galleries in India, to both serve the artists and enlarge the general appreciation of contemporary art.’

In recent years, a new generation of gallerists has emerged to shoulder that challenge, crafting programs that speak to the globalized world. In 2010, Amrita Jhaveri, formerly head of Christie’s India, along with her sister Priya Jhaveri, founded Jhaveri Contemporary in Mumbai, with a focus on intergenerational and interregional associations. It represents diasporic artists, such as Yamini Nayar, Rana Begum, and Simryn Gill, who explore place-making and belonging. Project 88 was founded in Mumbai in 2006 by Sree Banerjee Goswami with an eye for experimental works: its artists include Himali Singh Soin, Neha Choksi, Rohini Devasher, and Desire Machine Collective, revealing a trajectory quite removed from that of Goswami’s mother’s Modernist-focused Galerie 88. GALLERYSKE, in New Delhi, was originally opened in Bangalore in 2003 by Sunitha Kumar Emmart. It focuses on conceptual living artists who work with material, sound, and process – with Sheela Gowda, Astha Butail (winner of the fifth BMW Art Journey), and Dia Mehta Bhupal among them. Priyanka and Prateek Raja dismantled existing artworld hierarchies when they launched Experimenter in Kolkata in 2009: it represents major names like Magnum photographer Sohrab Hura and 2018 Turner Prize nominee Naeem Mohaiemen, while also functioning as a dynamic incubator and knowledge generator.

Installation view of Rana Begum at Jhaveri Contemporary, Mumbai, September 2019. Photo by Mohammed Chiba. Courtesy of Jhaveri Contemporary, Mumbai.

‘In the past 20 years we have seen tremendous progress and professionalism by Indian galleries – from formal representations of artists to innovative practices of showcasing their work through out-of-the-box and collaborative avenues such as gallery weekends,’ says Manjari Sihare-Sutin, Head of Sale, Modern and Contemporary South Asian Art at Sotheby’s. Sihare-Sutin attributes the growth of the Indian art ecosystem to the efforts of commercial galleries: ‘They are the talent spotters, the nurturers, the first patrons, the influencers.’

Vitalizing the scene and emboldening artists to realize projects beyond the commercial-gallery framework is a range of residencies, fellowships, and awards made possible by nonprofits such as Khoj International Artists’ Association, Mumbai Art Room, Indian Foundation for the Arts, and Inlaks Shivdasani Foundation, which has in recent years partnered with ISCP in New York, the Delfina Foundation in London, and Goldsmiths, University of London, among other organizations. ArtTactic’s inaugural India: Art and Philanthropy Report in 2019 tallied the number of new non-commercial platforms for Indian contemporary artists as having more than doubled since 2009. These platforms encompass art biennials, artist residencies, and new museums, with support coming from both private and corporate philanthropists, as well as foreign cultural consulates including the British Council, the Swiss Arts Council – Pro Helvetia, and the Goethe-Institut. This spirit of perseverance and ingenuity, shaped outside the state, has bred freedom and ambition to harness contemporary culture alongside mutual cooperation between public and private players.

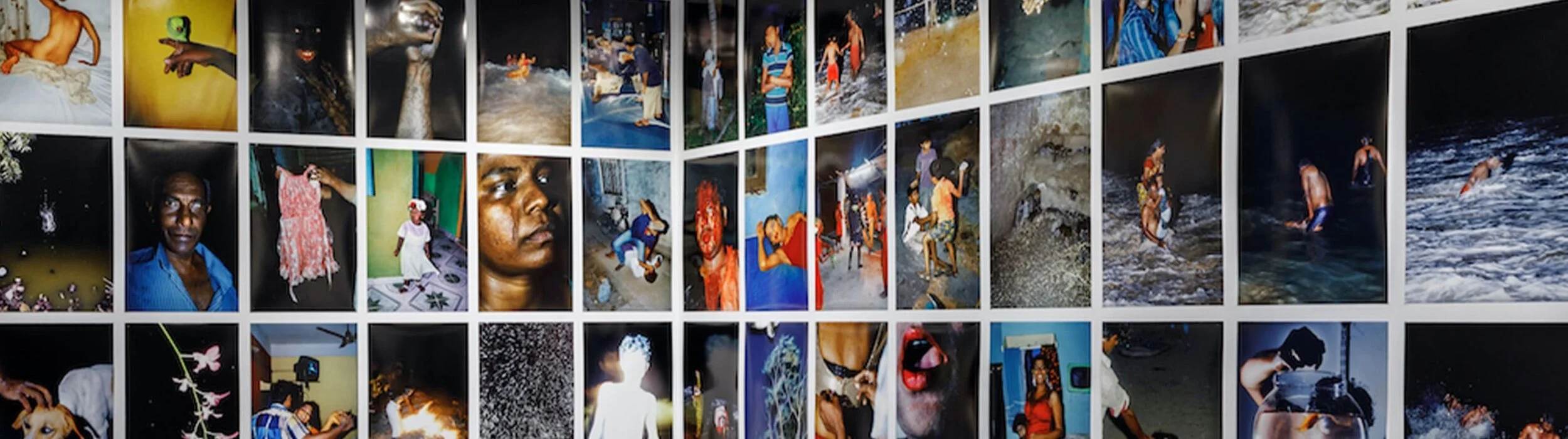

Detail of an installation view of works by Sohrab Hura, Experimenter, Kolkata, November 2020. Courtesy of Experimenter, Kolkata.

Today, Experimenter’s founders are focusing their efforts on their gallery being more of an ‘enabler’ than an agent, proposing a commercial-cum-institutional model that has grown from the context in which it operates. ‘There are many artistic practices that are severely underrepresented, and hence there are irregularities in the landscape that are inherent in how things have developed in India,’ they explain. Informed by this understanding, they launched the Generator Co-operative Art Production Fund during the pandemic to provide micro-bursaries for artists needing to complete projects, get production going, or start research. The idea began in conversations with artists on how to upend the power dynamics of traditional grant structures by introducing collaborative, humane, and cooperative frameworks with ‘no expectations of anything in return,’ the Rajas say. ‘It is this kind of form-challenging thought that propels us to question the frameworks we inherit.’