The 56th Venice Biennale opened on 9 May to much fanfare and the attendance of an array of art world celebrities and others curious to be at one of the world's most imaginative representations of nation states. Unfortunate enough to have missed the opening, and compelled to voraciously read reviews and news on the exhibited works (top lists and what not), I decided to investigate the emerging identity of the South Asian sub-continent through the makers of two distinct exhibitions.

The Biennale's main exhibition is explored under the overarching theme of "All the World's Futures" curated by Okwui Enwezor as a constellation of "filters" that grapple with the current "state of things", even if contrary to how they appear. How do art world practitioners position themselves and their responses to the upheaval of our times?

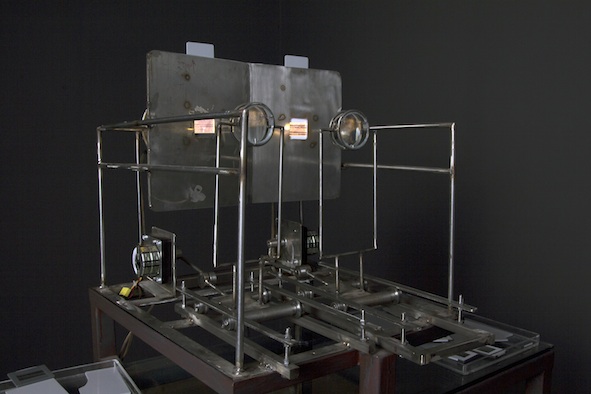

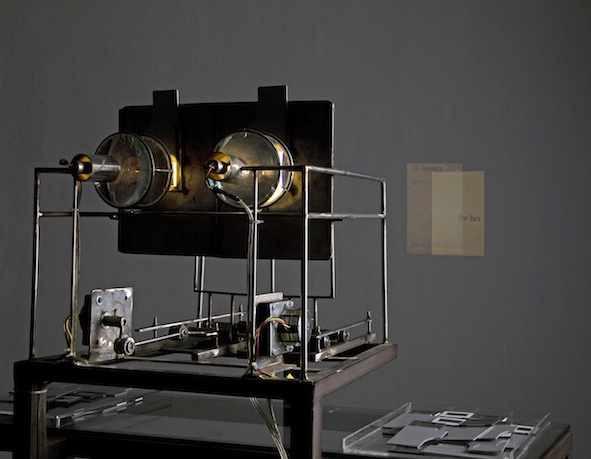

In the absence of national pavilions, Indian, Pakistani and Bangladeshi artists find themselves in the The Great Game at the Iran pavilion and in the collateral project My East is Your West hosted by the Gujral Foundation. The Iranian Pavilion includes the works of over 40 artists from the regions of South and Central Asia, addressing the notion of Asian supremacy through a series of socio-political engagements. For better insight, I reached out to Priyanka and Prateek Raja of Experimenter Gallery, who have three of their represented artists showing at the Pavilion. I wanted to know more about the inclusion of works by Naeem Mohaiemen, Bani Abidi and Raqs Media Collective and how said work reinforced South Asian identity.

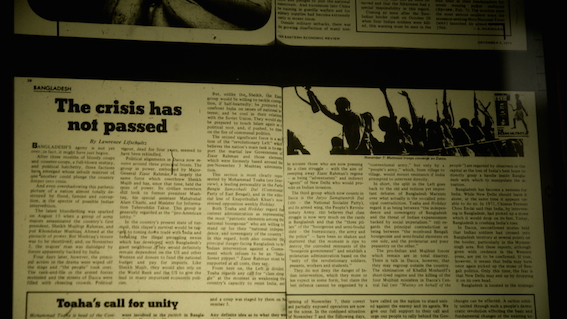

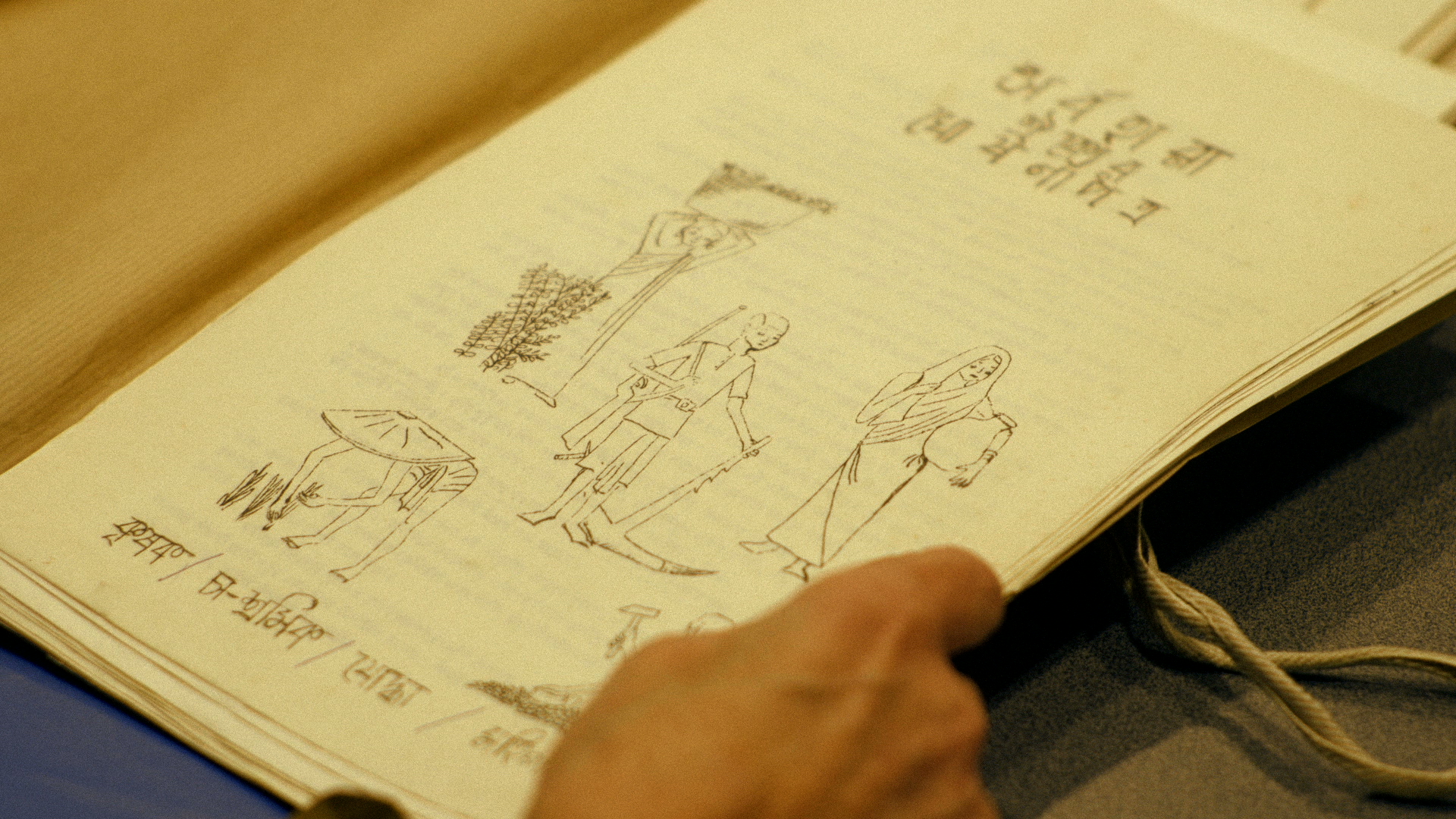

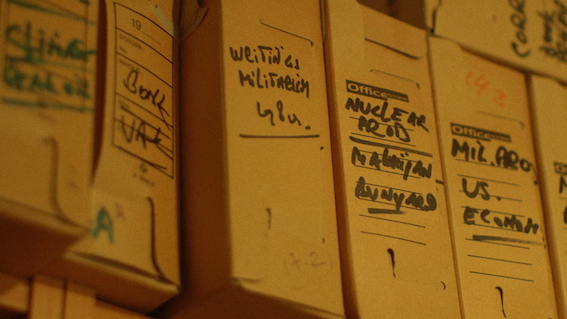

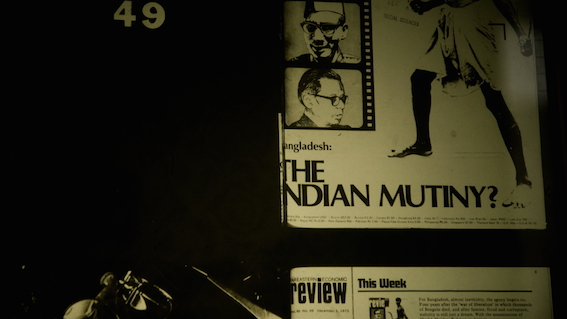

The duo said that South Asia is currently poised at an interesting juncture: emerging as the new center of the global economic order, coming to terms with the post-colonial moment and confronting new voices from the masses. At the same time, it is also coming to terms with the costs of growth and with the long-term impact of urbanisation, ecological challenges and preservation of the old. "Naeem Mohaiemen (Bangladesh), Raqs Media Collective (India) and Bani Abidi (Pakistan) have addressed issues of political history, ideas of power, that of security and of identity, of fragmented utopia/dystopia slippages in histories of regimes and governments established in the '60s and '70s in the "Global South". The inclusion of these artists reinforces the importance of recognising this history and in giving this time of South Asia a global voice."

The Biennale’s main exhibition is explored under the overarching theme of “All the World’s Futures” curated by Okwui Enwezor as a constellation of “filters” that grapple with the current “state of things”, even if contrary to how they appear.

A similar voice reinforcing South Asian identity is echoed by Feroze Gujral in a chat about the Gujral Foundation's project and her choice of selecting two artists: Shilpa Gupta from India and Rashid Rana from Pakistan. Imagined as a jugalbandi, a musical duet, a clapping of two hands together, both artists (one man and one woman) immediately came to mind for their works that subvert the idea of fixed borders and stark nation-state politics. Gupta with her poignant and minimalist aesthetic contrasted with the grandeur and spectacular presentation of Rana's works were a perfect way to make a strong, singular comment. Incidentally, both artists' work, alongside those of Riyaz Komu, Amar Kanwar and Hema Upadhyay are also part of The Great Game.

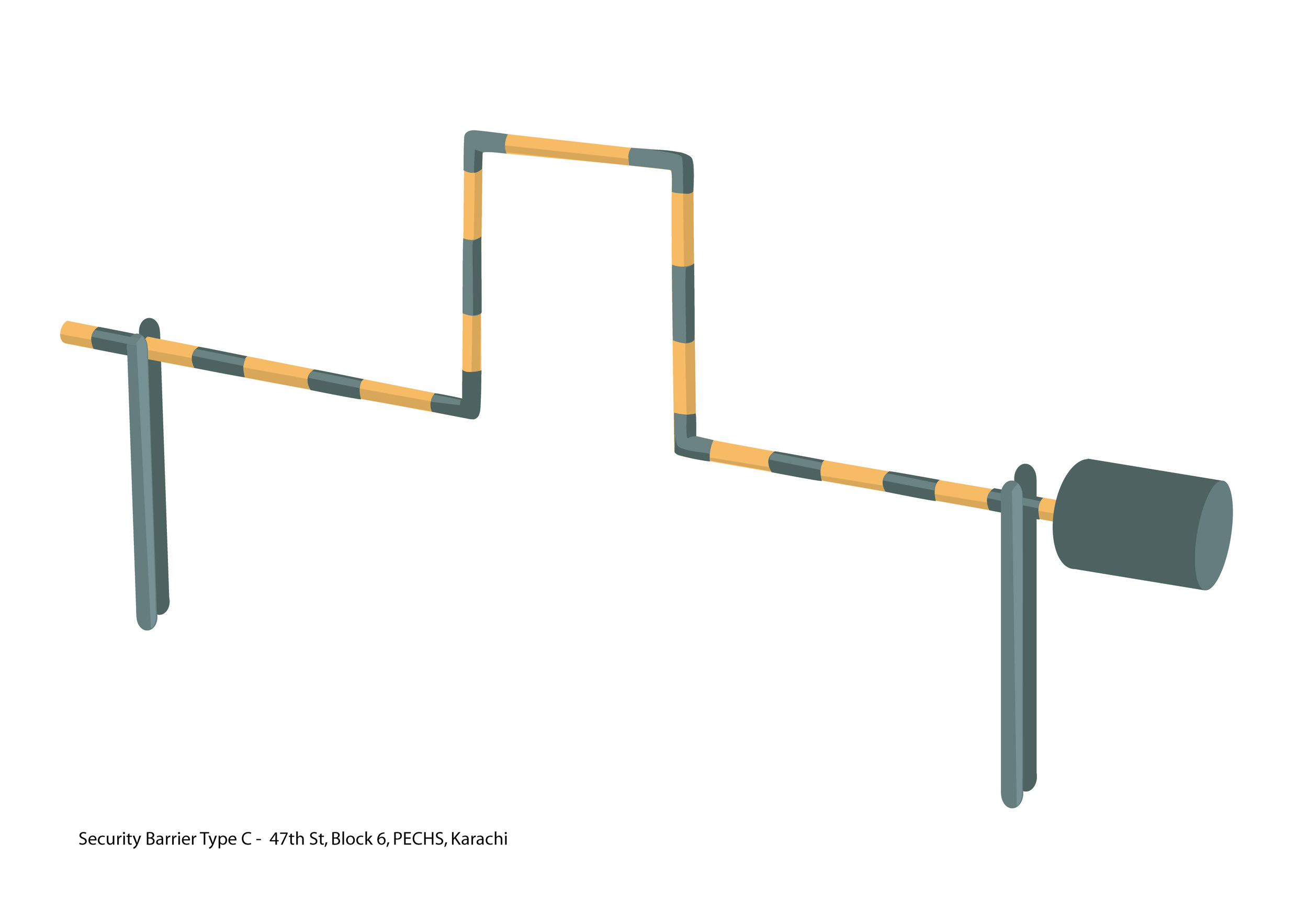

Curatorial advisor Natasha Ginwala explained how the Palazzo Benzon worked as a space to host the show: "The interconnected rooms in intimate scale and the decorative ceilings are activated by Rashid Rana's works across mediums of digital photomontage, interactive video and installation. Rana deliberates upon site-specificity through notions of location and dislocation as well as mirroring of people and sites by creating a live connection between Venice and Lahore." A similar connection, she said, was forged in Gupta's series Untitled (2014-15) between India and Bangladesh. "They are made in a range of mediums from drawing, photography, sculpture and video to performance and form a narrative exploring the India-Bangladesh borderlands and the precarious lives of communities around the border fence being built by the Indian state between the two countries. "

I asked Shilpa Gupta about how she positioned her work within the politics of the nation-state and its projections of statehood inside and outside territorial boundaries. Gupta told me that in her opinion, any kind of definitions are limiting and that My East is your West, based on one of her earlier light installations, are about this problem. "Incorporating 'light', a very primal element associated with vision, the artwork deals with perception and ways of looking from different sites of being, be it physiological or geographical. In a world where distances and contexts can generate non homogeneous selves, the work celebrates multiplicity while also suggesting an ever present possible deception in the any permanent / singular kind of positing."

Rashid Rana was similarly optimistic about the role of artistic interventions in developing a progressive inter-state politics.

"I don't know if a very direct message ultimately translates into measurable action but I think the fact that art can create meaning even beyond specifics helps challenge internalized assumptions about the world. Being an idealist, I hope that in distant if not immediate future the subcontinent becomes a region akin to the European Union where individuals and ideas are able to move freely."

It is noteworthy to mention the funding, infrastructure and experience that go into hosting projects of this nature. Usually built by corporate foundations, putting together teams of individuals or private foundations that are passionate about the arts to support such initiatives is a task in itself. The Iranian Pavilion is supported by the FFF Faiznia Family Foundation in collaboration with the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art, while My East is Your West is hosted by The Gujral Foundation, with support from the likes of the Lohia Foundation, Serendipity Arts Trust, Rajan Anandan and Radhika Chopra of Google (India) besides supportive galleries, funding bodies and a huge gathering that provided moral support.