oth still and moving images stimulate emotive reactions and tickle our perceptual appreciation: be it news media with a barrage of sensational imagery, cinema with a plethora of dramatic narratives, documentary photographs, family albums or landscape images.

Susanta Mandal is interested in what he claims is the "slippery zone" between still and moving moments captured in images. An element of playfulness and a pinch of irony exist in almost all his works. Through his art, he explores the mechanics of motion in a controlled environment of his own making through a series of devices, better known as kinetic sculptures.

Mandal graciously agrees to walk me through his ongoing exhibition Hard Copy at Vadehra Art Gallery in New Delhi. As we chat, he takes me back to the experiences that have inspired and driven his art practice. Owing to poor eyesight right from his early childhood, Mandal confesses to having tried to examine things more closely, often squinting to see more clearly. It is no surprise then that Mandal uses multiple lenses and magnifying glasses in his work. This fascination furthers an interest in methods of scrutiny: how close can we observe something to be able to understand its nature? And then again, what are the things that we choose to focus on? His earlier piece titled It's a Routine Scrutiny from 2006 is an assemblage of photographs that is magnified (in part) by a magnifying glass that moves linearly in front of the images, highlighting a face, whole or partial, part of text or an object in the background, depending on what falls behind the glass. Quite obviously then, it questions observances of the mind's eye.

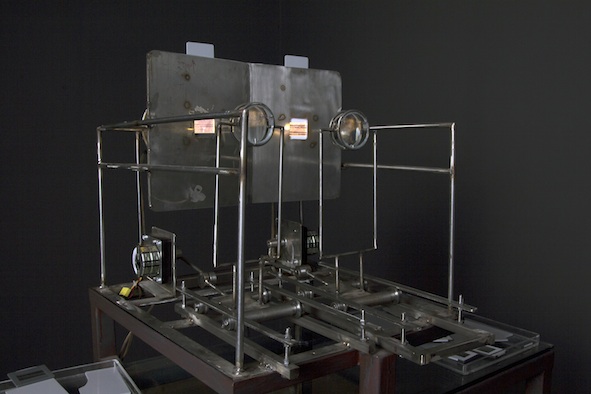

While delving into the manner in which we read images: what they record and how they in turn are archived, Mandal began to study the devices that captured and projected images; cameras, image projectors and film paraphernalia. Aesthetically, Mandal's sensibilities lean toward an acute geometric minimalism. His use of light and shadow poetically highlights his preoccupation with the minimal and subliminal, with nostalgia and fragility.

Modeled along the lines of the 17th century image projector, the triptych Magic Lantern is made up of three kinetic sculptures, each projecting an image from a slide: of a landscape, a home and a child. Mandal informs me that although the subject matter of the photograph is not the focus of his work, all three images draw from fond memories. All in all, the exposed mechanics of the projector-sculpture, the hum of the moving image and the light that helps us focus in the dark gallery room make for a rather surreal experience.

Owing to poor eyesight right from his early childhood, Mandal confesses to having tried to examine things more closely, often squinting to see more clearly. It is no surprise then that Mandal uses multiple lenses and magnifying glasses in his work. This fascination furthers an interest in methods of scrutiny: how close can we observe something to be able to understand its nature?

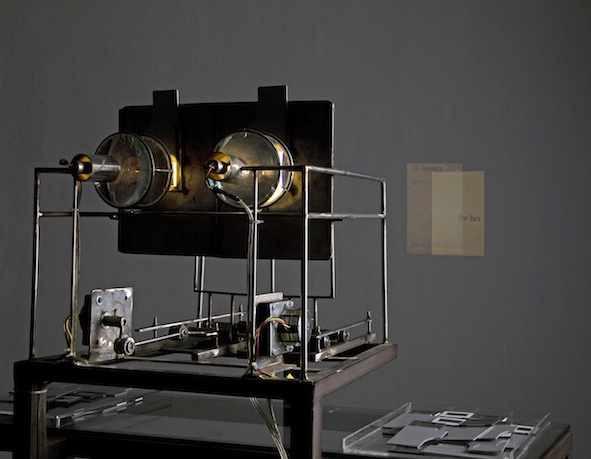

A meticulous and precise process of calculations is involved to ensure a specific speed of movement, a degree and focus of magnification and a timely sequential repetition of each image. To this, Mandal adds a deliberate tension, where the mechanics of each device is programed to an almost perfect score, allowing for the 1% element of chance. This keeps the viewer intimately and somewhat pensively engaged.

Another piece in the inside room plays off our understanding of language, and of words. Again structured with lenses and focused light, the slides projected this time feature words extracted from official letters that are erased or scrambled to open up new meanings. Three slides overlap each other, lit planes on a dark wall emerging from the inverted reflection of the slides in the device, which itself casts shadows of its own.

None of the works in the show are individually titled. They are all filed under the show's title Hard Copy, an obvious pointer to digital technologies and their mediums of storage. Positioned at the intersection between mechanical, digital and biological engineering, the show opens with a series of drawings of computerised tests of the human eye, leading to a minimal structural piece framed as a square of pipes, with a magnifying glass with a spotlight focusing on a specific area. On looking hard enough through the magnifier, I sense a motion, almost like a vibration. Whether it was my wanting to see some activity to explain the focal point of the work or an anxiety of not being able to see anything through the glass that was different from the rest, I certainly did sense an energy.

The last piece of the exhibit is a display unit of Mandal's process of art-making. A drawing board with small sketches, lenses, again the play of light and shadows, all placed in an open vitrine cabinet where one can peer in to yet again "see" and scrutinise.

Hard Copy remains on view at the Vadehra Art Gallery until 18 May, 2015.