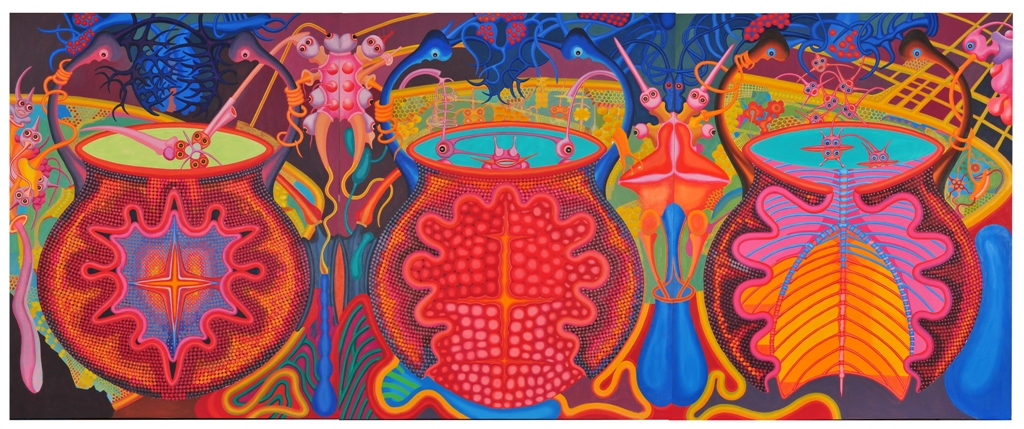

Pradeep Puthoor's art is a confluence of artificial intelligence and biological engineering represented on canvas with vibrant colours and intricate detailing. Adorning the walls of Nature Morte gallery this month is a series of large canvases, executed in the last two years. As I view each, I am transported into a giant chemical reactor comprising metal vessels with the attendant paraphernalia, ranging from tubing and pipes, oozing and bubbling fluid, organic tissue combined with skeletal parts, often against a backdrop of digital codes, metamorphosing into hybrid alien forms of a fantastical dimension. It is an onslaught on the senses, but I suspect that to be the desired reaction from the viewer. Wedged precariously between the real and imagined, Puthoor's works appear to comment on the decadence of urban lifestyle and the human need for mutative technologies. At the same time, the paintings explore emotional underpinnings of fear and anxiety related to man's desire for immortality. With a touch of both surrealistic and futuristic elements, Puthoor's paintings wryly prompt to question our faith in a projected realm of fantasy and science fiction by distorting reality as we know it.

The exhibition is simply yet aptly titled 'Pradeep Puthoor: New Paintings' and is the Trivandrum-based artist's first major solo show in Delhi, as well as a first showing at Nature Morte. Puthoor's skill as graphic artist and fine draughtsman is evident in each work. Upon close observation I notice an array of tribal motifs, fused and entwined in a modern madness of informatics. There is also a discernable sarcasm in these large and vulgarly bright paintings, which when displayed together create an immersive atmosphere, enveloping the walls and blanketing the onlooker's sight from all else. The visual monotony is broken by the few sculptures by Arun Kumar HG that punctuate the different rooms of the gallery space. Their inclusion here ironically speaks of another level of human relationships with nature, evident in the forms of the revered cow Nandi or that of a juicy oversized watermelon. Out of place and rather disturbing amongst this scheme is Palmscape, one of Mrinalini Mukherjee's marvellously moulded bronze sculptures, which sits atop a pedestal at the far end of the exhibition.

As I survey the gallery, a large triptych in the basement titled Night Watch with Dolls strikes me as hauntingly dark, in colour and form, hung next to a much paler painting titled Temple of Yellow bones. The corner conclave of both these works sums up the exhibit for me, as a meeting of yesterday and tomorrow, of anatomical and robotic compositions, of urban and cosmic spaces.