What do Jawaharlal Nehru and Alfred Nobel have in common, I wondered, as I stumbled upon the traveling exhibition The Nobel Prize: Ideas Changing the World, on view as a temporary exhibit at the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library, located in the heart of the city. Both were iconic figures who left a lasting legacy that has redefined our knowledge of history and the ways we choose to "read" it today. Surrounded by much controversy and fanfare, both are remembered and memorialised in very different ways.

Located at the corner of Teen Murti Marg, one enters the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library through the gate to the Planetarium, past a 14th century hunting lodge belonging to the Delhi Sultanate ruler Firoz Shah Tughlaq, finally leading to the sprawling lawns surrounding the former residence and now memorial museum of Jawaharlal Nehru. As I walked in, I was struck by the many timelines of existence: past, present and future, all collapsed into a moment of experience and a site.

Museums were developed to preserve material culture associated with a civilisation, person or event. Memorials and monuments have been built for centuries in the hope of attaining glory and immortality for the persona being memorialised. Re-tracking back to the "frame" of the Nehru Museum, the idea to preserve and foster the history of India's independence through the figure of one of its leaders isn't new, and is not wholly comprehensive. The Nobel Museum, on the other hand, commemorates Alfred Nobel's wish to foster and award innovation in fields he appreciated — physics, chemistry, literature, peace and medicine. Call it philanthropy or a way to redeem himself from a then-notorious reputation as the inventor of dynamite. His name perpetuates because of the one will and wish that ensured universal approval and his continued veneration thereof. While in concept, both museums rely on the personalities from which they derive their name and inspiration, the difference between the two lies in the outlook: NMML looks retrospectively, while the Nobel Museum looks at the "now" and the future.

I find it pertinent to observe what is let in and what is left out. Criteria for inclusion have always played politics in the writing of history and in the collective memory of the public.

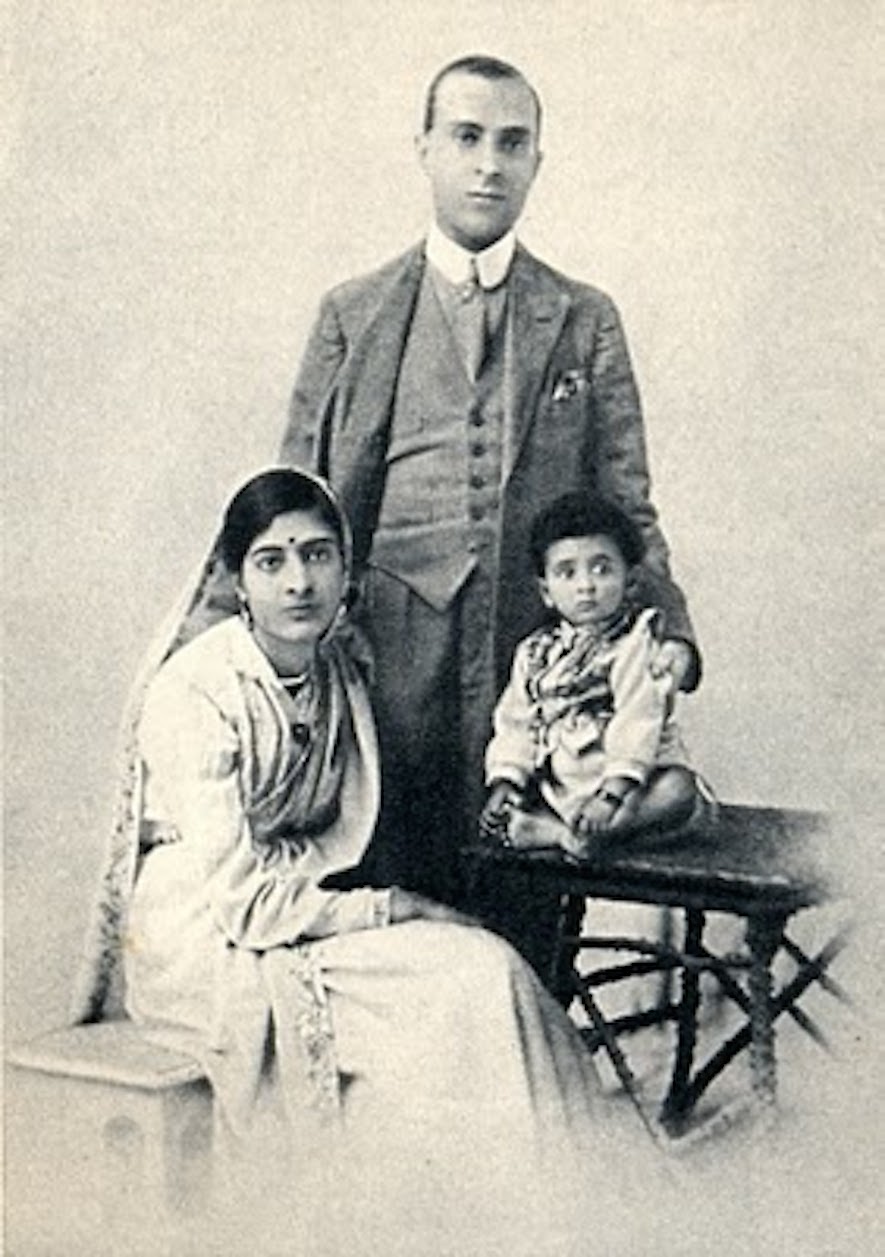

In room after room of the NMML, I see Nehru family albums, documentary photographs of socio-political events that are regarded as critical historical moments and newspaper clippings recording the same. Constructed genealogies of movements are displayed on the wood-panelled walls of the building. Each reveals its own history – recorded in the architecture, the construction, the use, the contents, the customs of visitation and the public's perception.

The Nobel Prize: Ideas Changing the World exhibition is located on the first floor and balcony of the building, somewhat in the middle of India's history of the Satyagraha movement, leading to "Gandhi as Rebel". It is divided into the following sub-categories — "The Nobel Prize and its Inception", "The Prize over the Decades", "The Prize in Everyday Life" and "The Prize in the Future". The first chapter is illustrated with a selection of three winning innovations in each of the five fields, as well as Nobel's own counterpart. For example, in the vitrine for the field of medicine, Nobel's transfusion device is placed alongside Robert Bárány's vestibular apparatus (1915) and Shinya Yamanaka's model of reprogrammed mature cells (2012). The second chapter is illustrated with edited videos clips, marking "defining" events in history — the fall of the Berlin Wall for the decade 1981-'90, the widespread use of the transistor radio in the 1950s, the founding of the Red Cross in the 1920s. The third chapter is an extension of the first two, with a description of how Nobel laureates' innovations affect us. The last chapter is an interactive poll asking the visitors questions about their views on disarmament of nuclear weapons, on climate change and the use of natural resources, medical research and ways of increasing human longevity as well as the importance of storytelling in an age of digital media.

So what does my argument have to do with art per se? Well, for one, I think it is important to note the manner in which we understand museums and the personalities behind each exhibition. It also brings to the fore the reasons and methods behind selection and collecting for display. With private museums in India playing a dynamic role in facilitating new ways of representation and a platform for initiation of open dialogue, I find it increasingly pertinent to observe what is let in and what is left out. Criteria for inclusion have always played politics in the writing of history and in the collective memory of the public. How far are museums and their intent derived from the biographies of their founding personalities, and to what extent have new mutations been formed by presenting certain documents and achievements within the elevated frame of artifacts for museum display?

The exhibition was fittingly inaugurated by Nobel laureates A.P.J. Abdul Kalam, Kailash Satyarthi and George Smoot, and remains on view at the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library till 11 December.