Art India (Issue II, 2016)

Man, Interrupted

G.R. Iranna’s mid-career retrospective presents the resilience of the human spirit, observes Kanika Anand

In an artist’s career, there arise distinct phases that punctuate the trajectory of his work. These phases are reflective of the artist’s approach, which for G. R. Iranna is based around the representations of the human figure – contorted, framed and subsumed. His introspections have led him to explore the human form in societal contexts as also a range of human desires and thoughts. Resistance and resilience are underlined in a series of compositions and sculptural installations in his mid-career retrospective titled And the last shall be the first, at the NGMA, Bengaluru, from the 16th of February to the 20th of March. The show, curated by Ranjit Hoskote, comprises works produced over a twenty year period from 1995 to 2015, introducing us to work that delves deep into the make-up and interiority of the human psyche.

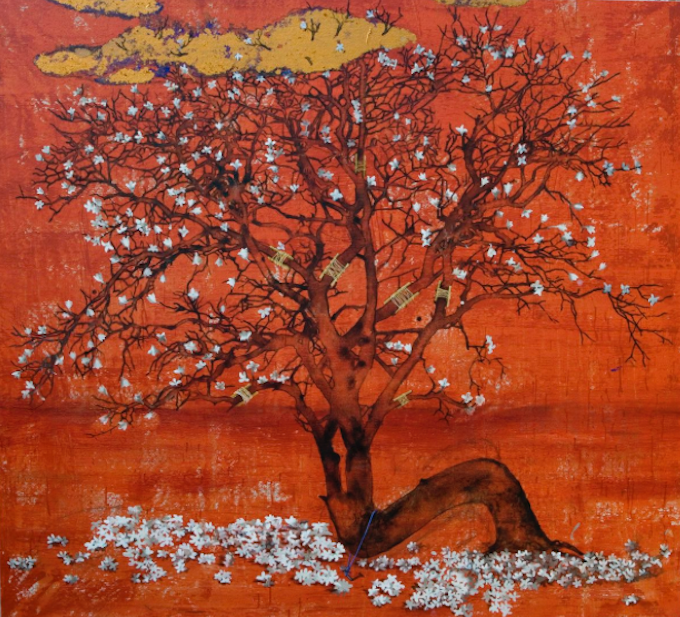

German cultural theorist Peter Sloterdijk’s essay Rules for the Human Zoo (1) explores, among other issues, the various ways in which human beings have tamed their animal natures – what he calls the “engagement of retrieving man from the barbarian”. Sloterdijk prescribes some minimally effective methods of self-taming that find resonance in Iranna’s repetitive imagery, featuring the acrobat, ascetic, monk, virtuoso or the Buddhist Master. Each of these roles points towards our society’s need to civilize the ‘human zoo’. It is in paintings like Scaffolding Peace (2010) where an emaciated, naked figure, perhaps of the Buddha, is seen being held captive insidea construction scaffold that we witness the artist’s angst in coping with repressive norms. In Tempered Branches (2013) and Forced Autumn (2015) it is the artist’s intention to underscore the wisdom tree as a witness to the activities around it – violent and joyous. A close-up view of its upturned branches in the latter painting suggests the artist’s desire to subvert the tree’s natural growth pattern to highlight the stifling nature of urban dystopia. Iranna’s compositions often remind you of theatrical tragedies where the subject assumes the role of a victim and engages the audience by drawing on its empathy.

Owing to his background of growing up in a village in Sindgi, Karnataka, and observing liberal Lingayat traditions that conceive of the self as emerging from and being in union with the divine, the forms and symbolic bearings of Iranna’s work do not surprise. Apart from the human figure, Iranna’s subjects are from the natural world where the artist is part-rehabilitator and part-provocateur. See, for example, the remodelled, bandaged vessel in Dragged Boat (2009), an engineered branch in Moving Plant (2012) and a donkey carrying bandaged agricultural ‘weapons’ in Wounded Tools (2008).

The show includes twenty-four paintings and eight sculptural installations that are placed in two groups across two galleries in the museum. The first comprises works executed between 1995 and 2005 and the other between 2005 and 2015, tracing the evolution of his practice. Iranna’s choice of tarpaulin as a surface to paint dates back to his early student days at the College of Art, Delhi, where he chanced upon the material at the Azadpur market and decided to experiment. Tarpaulin is custom-cut to a specific size permitting the creation of large-scale works and can absorb multiple layers of paint owing to the weave of its surface. It allows Iranna to say multiple things at once, and offers a way to correlate the complexities of spatial and temporal existence.

Art and politics have employed the agency of gesture, which in its expanded sense, encompasses all the ways in which people confront each other and seek to evoke desired responses, whether by speech and expressions of body language or by the display of signs and signals in images, texts, music and architecture (2). The gesture of binding and controlling sensual impulses as well as the act of deliberate erasure punctuates Iranna’s perception of the world. In the sculpture Dead Smile (2007), a group of emasculated men whose faces are covered with black cloth, sit on their haunches – naked, subservient and held back presumably by force. In Silencer (2005), the male figures represent the collective consciousness of people who want to break free, whereas in The Birth of Blindness (2007), these abject figures kneel with their heads down, in prayer, penance or obeisance. This subjectivity is further explored in one of Iranna’s recent works [Gods and Guns, (Witness), 2015] in which a painted carpet features as a metaphor for tarnished traditions and old customs. It is a painting that can be hung sculpturally. Even as he plays with the form, Iranna succeeds in speaking of suffering and erasure, putting the spotlight on the artisan, the migrant and the victim.