Some places stir a sense of nostalgia. Some places leave us vacant. Some places delight us while some others disturb us.

A place to which we belong focuses on forms of mapping that communicate our sensorial experiences of remembering or imagining a place, as opposed to being within or outside of it. Informed by the multifarious relationships that individuals and collectives have with their environment, the exhibition questions our personal understanding of place as a filtered sequence of encounters that encompasses its own set of narratives, aesthetic textures and subliminal thoughts.

For Shalina Vichitra, land not only offers itself as a visual metaphor of lived experiences but also a tactile archive. Her paintings function as visceral geographical annotations and recordings that employ the tools of cartography to address the complex subject of 'belonging'. The fragile balance between natural world and human habitation surfaces through lines and markings that conventionally help organize or delineate. Underlining her practice are moments of movement, of journeying- through paths and routes, across or within boundaries, between past and present, with the suggestion of an alternative possibility. Her work thus, serves as an abstract rendering of a concrete reality.

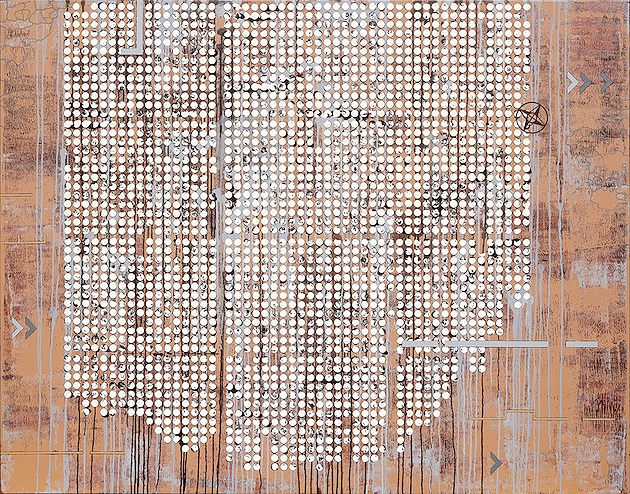

There is something subliminal about looking at the world from above- be it from a plane or the top of a mountain. The format of the aerial view divulges a plethora of earth patterns and temporal footprints, continually gathered and ever changing. Within it, Vichitra’s work lays bare the polarized values of high and low- of mountains and valleys, of skyscrapers and low lying buildings, of monuments and ruins, without the consequent knowledge of their respective dwellers or keepers. Her repeated travels across towns located in the Himalayan Mountains have fostered a visual vocabulary of geographies explored in works like Hamlet,Labyrinthand Unknown Origins.

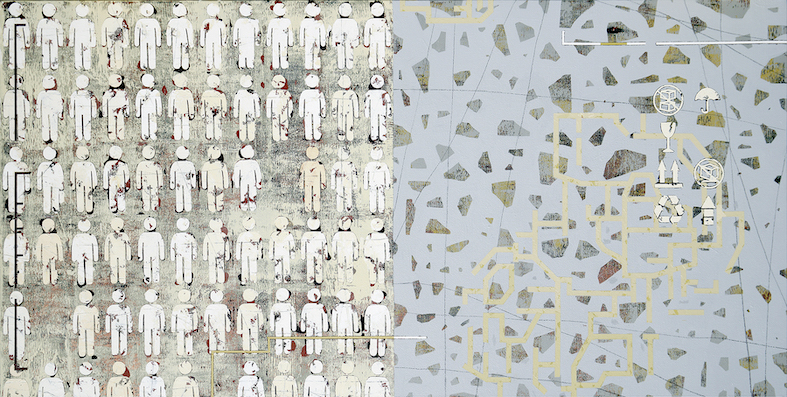

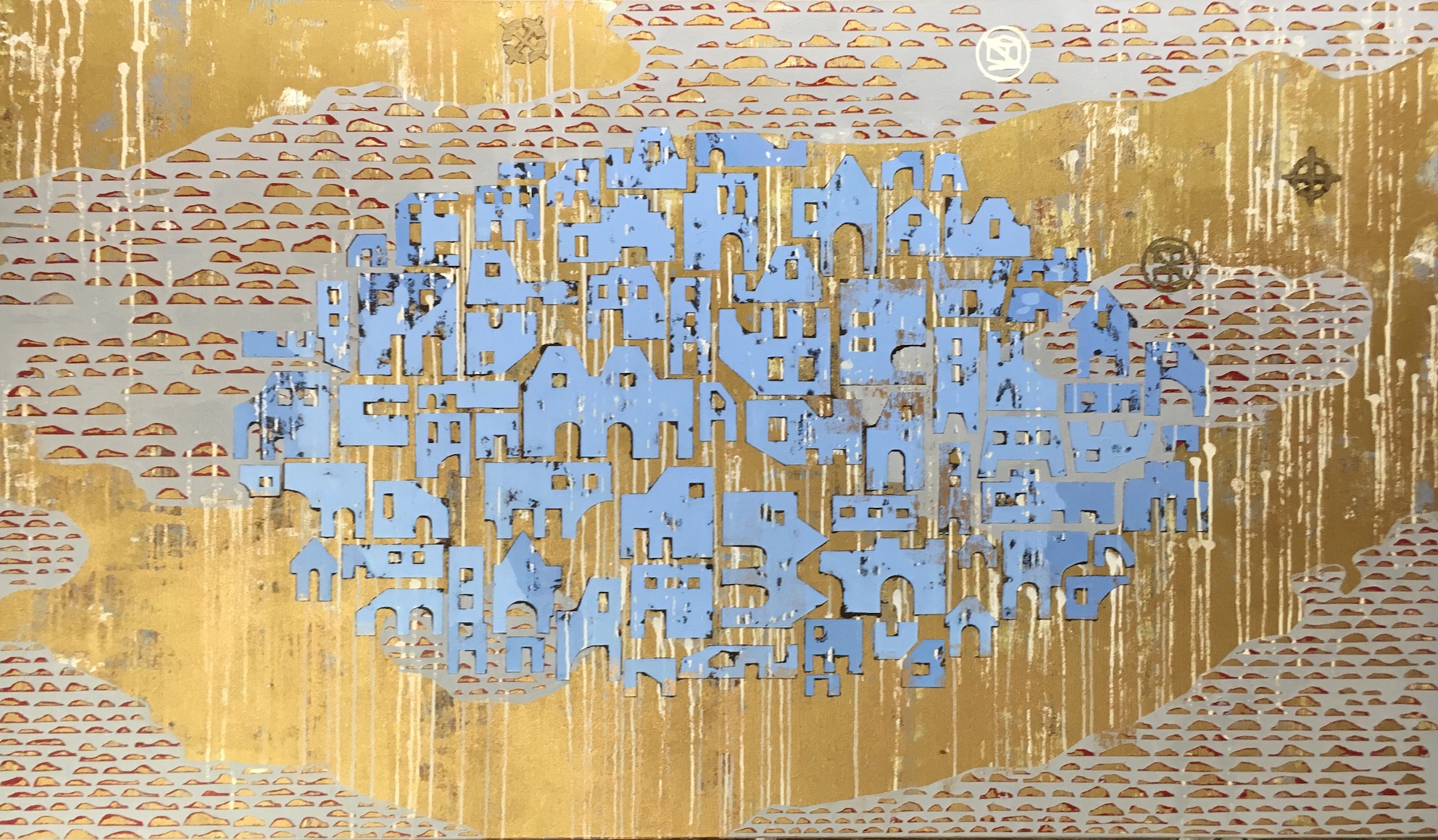

Peppered with archetypical outlines of people or dwellings, the artist proposes a template of an inhabited world, where man is stenciled into the landscape. The impressions of time are palpable in the treatment of the surface of the canvas, washed and dripping, the vestiges of an earlier layer peeping at us from under another. In Hamlet, as its title suggests, one sees a scattering of homes- or sections of homes, minus any distinguishing features. In Labyrinth, one is confronted with an equal division between the human multitude and a piece of land that is already marked with what appears to be the blueprint of a house on a mosaicked floor. Here Vichitra employs the standard pictorial symbols for ‘Handle with care’, ‘Fragile’, ‘Recycle’ to suggest a two-fold predicament- of responsible action when engaging with the environment, and of cultural preservation of the indigenous community. Most often used on packaging objects for consumption or travel, the symbols’ deliberate introduction reflects the artist’s emboldening intent to reference the objectification of land. With more distance from the surface, the silhouetted shapes of the human form are reduced to specs that together build and sustain a larger ecosystem. Unknown Origins harks to an unknown past owed to the rapid changes in the physiological makeup of land and our sense of place within it.

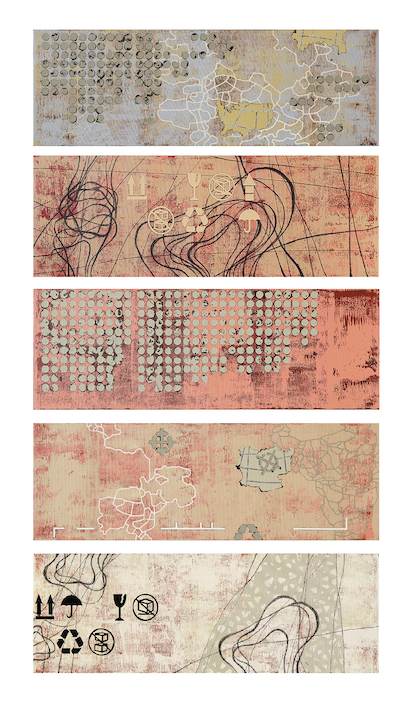

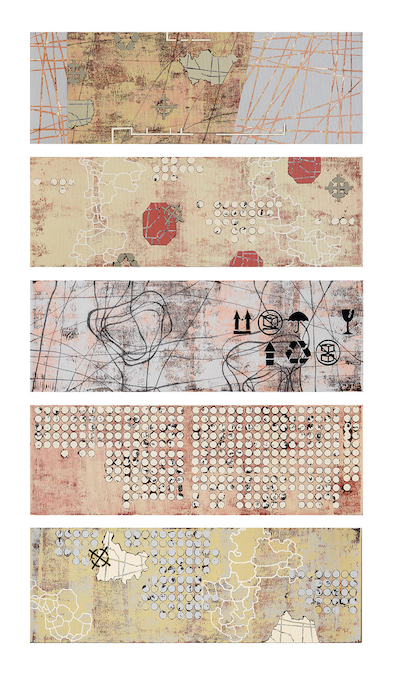

The anonymity and standardized language implicit in the stenciled forms function as place markers of non-representational topographies, so as to assume the work simply frames the surface of land- any piece of land where humans reside. In the twin series titled Endangered, 2018 comprising five panels each; Vichitra builds her composition vertically, like building blocks set one above another. The stacking is an interesting element in her practice, as also seen in the work- Witness, for it relates to modes of construction and development, and reflects a diversity of patterns in the overall fabric of land. The emotional appeal in the works is lucidly translated via their titles, emphasizing the fragility of not only a specific landscape, but also our own existence, for it is the surface of land to which we are bound.

The nebulous nature of our world is more starkly conveyed in Revisited, 2018. A dense settlement, where the sense of communal bonding is easily imagined, floats against a cloud of gold. The superficiality of the surface heeds a darker reality- of prolific multiplication of dwellings, at odds with the sanctity of the surroundings, and the incongruity of the community wanting to preserve exactly what they are invariably destroying.

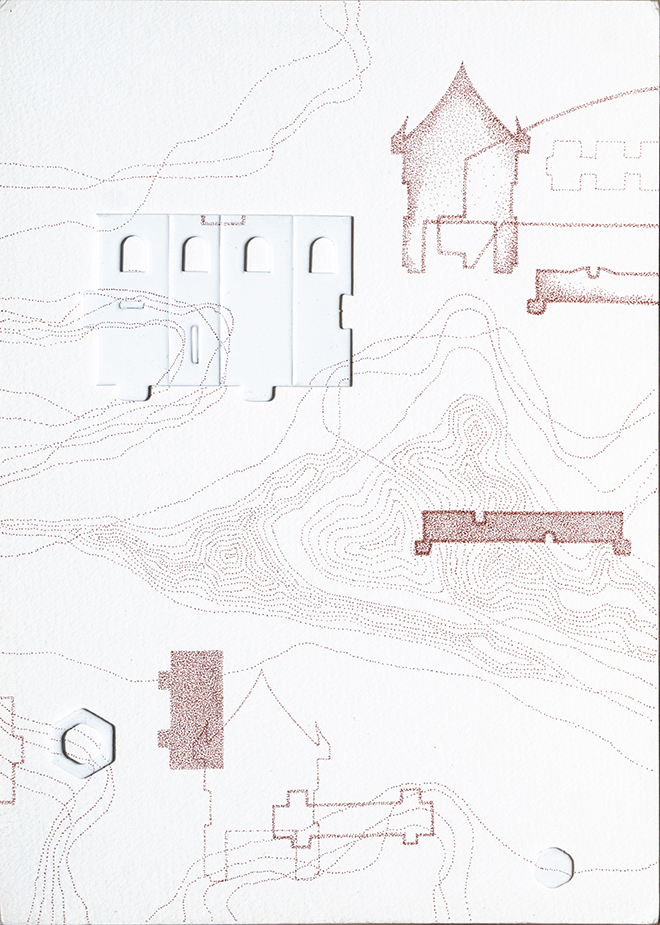

Drawing on Henry Lefebre’s Production of Space which views life in terms of a feedback loop between human activity and material surroundings, space is configured not as a container, but is continually ‘produced’ through activity. The cartographer’s tools of scales and symbols do at times, fall short of rendering the human aspect to places that cannot be verifiably surveyed or mapped. This inadequacy is cleverly resolved with the insertion of pieces of children’s puzzles into two suites of drawings that comment on popular and lost architectures respectively, that in turn attest to voids and structures being actively produced through human activity. The first suite titled Perfect-Imperfect draws on two cities that owe their fame and consequently large visitor numbers to the monuments that are located within their boundaries- the Taj Mahal in Agra, and the Leaning Tower of Pisa in Pisa. In the vein of loss and failure aligned with the intent behind their building, these two sites enjoy rather curious histories and have been at the center of many a controversy. The work is an ironic play on the geometric perfection of these monuments where generic architectural elements like arched gateways, domes, and columns are arranged to comment on the beauty of imperfection.

Destruction often preserves the memory of what is destroyed. Such is the case of the Medical College situated on top of the Chakpori hill that was destroyed during the Chinese invasion of Lhasa in 1959, only to be replaced by a TV tower. Connecting the sacred hill to the one on which sits Lhasa’s Potala Palace are now a string of prayer flags, a visual metaphor that bridges the distance between the lost and existing cultural sites. Deconstruction is a playful re-construction of the past and present, where fragments of these emblematic structures are gathered and presented in the second six-part suite of pen drawings. The workreflects the alternation between destruction and creation as an existential cycle that brings not only despair, but also reason for hope and strength.Both sets of drawings perform a mediating role—between epochs, traditions, and cultures, where the paradoxical qualities between violence and beauty co-exist on the same surface.

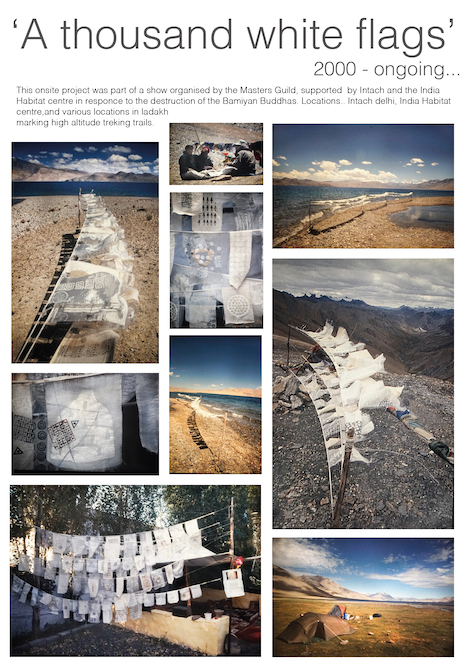

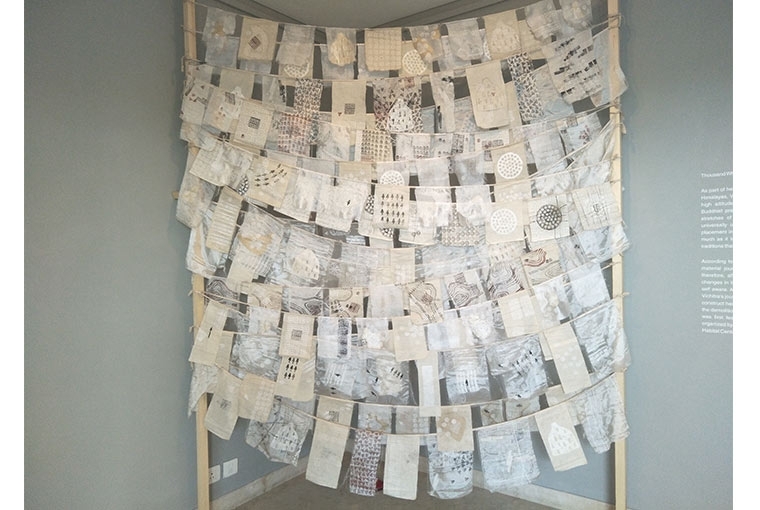

As part of her ongoing engagement with the mountain land of the Himalayas, Vichitra has since 2000, been placing white flags on high altitude sites and along trekking trails. Reminiscent of Buddhist prayer flags or cloth banners strung to bless the vast stretches of land beneath them, and of white flags that are universally understood as a symbol of peace, their consistent placement in the land is a symbolic gesture of peacekeeping as much as it is the planting of geographical footnotes embodying traditions that refuse to die. According to British archeologist Christopher Tilley, walking is a material journey where the physical body is immersed in and therefore, affected by the environment- say by time of day, by changes in the terrain etc. making the person walking extremely self aware. A Thousand White Flags, (2000 - present) represents Vichitra’s journey where spatial and temporal ‘presents’ coincide to construct her own process of archeology. Begun as a response to the demolition of the Bamiyan Buddhas in Afghanistan, the project was first featured at the exhibition And Buddha Smiles Again organized by the Masters Guild, supported by Intach and The India Habitat Centre, New Delhi in 2000.

As a final ode to her learning, or ‘an offering’ as Vichitra describes them are a row of nine prayer wheels, patterned in her visual language with an array of symbolic markings that speak of the land she has observed and the land left uncharted.

Kanika Anand,

March 2018

References:

- (ed.) Árnason Arnar, Nicolas Ellison, Jo Vergunst, Andrew Whitehouse.Landscapes Beyond Land: Routes, Aesthetics, Narratives, 2012

- Cruz-Pierre, Azucena & Landes, Donald A. Exploring the Work of Edward S. Casey: Giving Voice to Place, Memory, and Imagination, 2003

- Lefebre, Henri. The Production of Space, 1974

- Pellitero, Ana Moya. The phenomenological experience of the visual landscape. Research in Urbanism Series, [S.l.], v. 2, p. 57-71, Sep. 2011. ISSN 1879-8217.

- Tilley, Christopher. A Phenomenology of Landscape: Places, Paths and Monuments, 1997

- Tuan, Yi-Fu. Romantic Geography: In search of the sublime landscape, The University of Wisconsin Press, 2013