With the support of the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art (KNMA), Tate Modern holds landmark exhibition of key figure in 20th century painting.

According to Indian modernist Bhupen Khakhar, “Truth is Beauty and Beauty is God”. The Tate Modern provides an opportunity to discover the artist’s extraordinary work and inspirational story, bringing together Khakhar’s work from across five decades and collections around the world for the first time since his death.

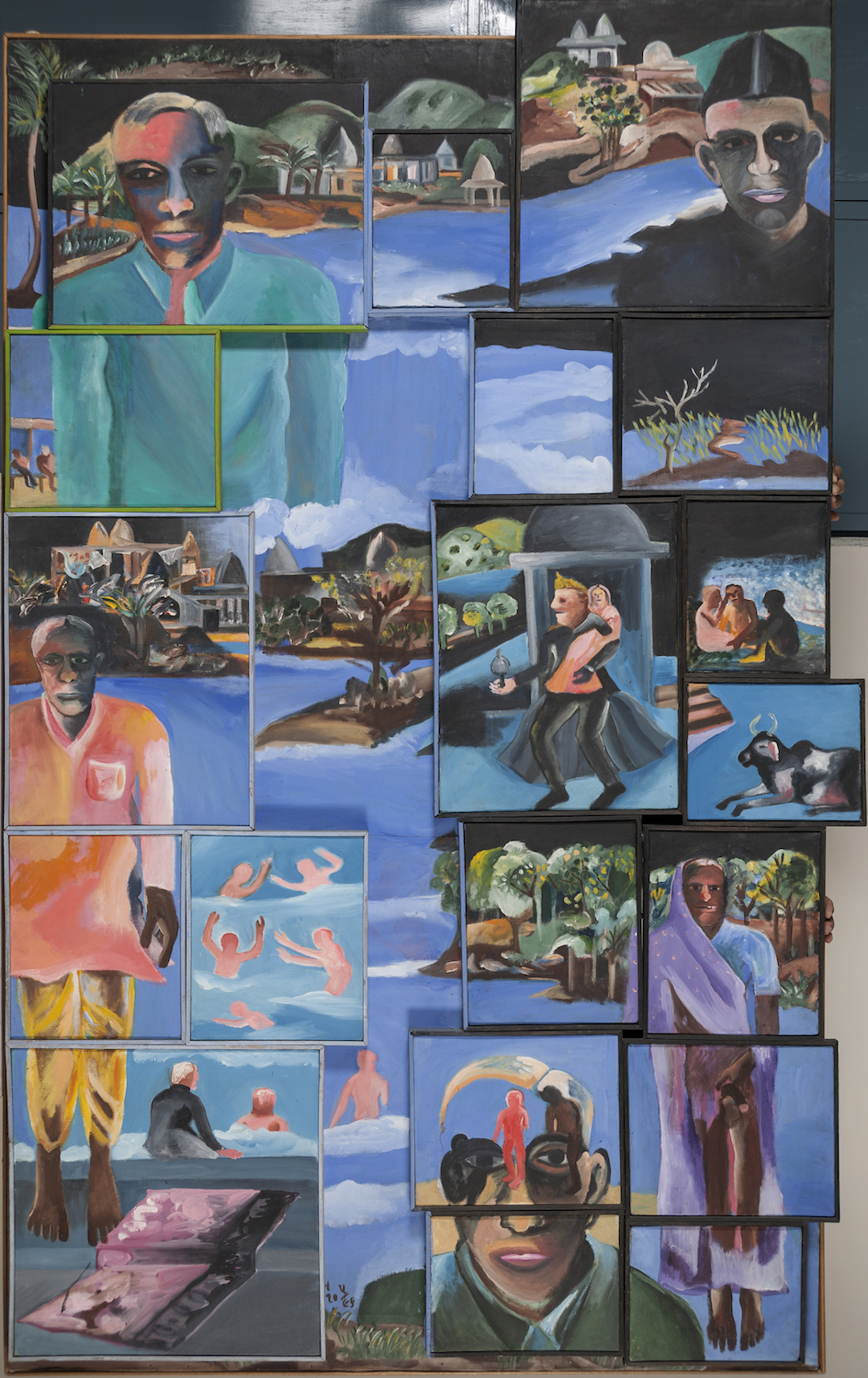

Bhupen Khakhar, “You Can’t Please All”, Tate Modern, 2016, installation view. Left to right: ‘Jatra’, 1997–9, oil paint on canvas, 177.5 x 239 cm; ‘Yagnya or Marriage’, 2000, diptych: oil paint on canvas, 173.5 x 346.6 cm. Image courtesy Tate Modern.

Truth is Beauty and Beauty is God, a self-authored catalogue accompanying the London exhibition, not only explains many of Bhupen Khakhar‘s works, but also their essence and his overall worldly vision. Largely drawn to Gandhian philosophy, he sought the truth through honest representations of the world and through the mundane humdrum of ordinary life. It is, of course, in retrospect that we fully understand the place of this man and his art.

The past month has seen many a review, including the infamously critical piece on The Guardian rousing reactions from many in the art community who have since made it a point to ‘correct’ opinion on Khakhar’s work. For an artist who lived most of his life as an accountant, who was homosexual in a conservative family (and society) and who chose to use the surface of the canvas as a confessional space, the drama that unfolds alongside the exhibition is somewhat similar to the social theatre that Khakhar had grown accustomed to and parodied. At his first international showing since 2003, Art Radar refocuses on the makers of the exhibition, the institution that hosts it, the critics and commentators, and the artist who has kept them all at work.

The Bhupen Khakhar retrospective “You Can’t Please All” opened on 1 June 2016 at the Tate Modern, supported by the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, and runs until 6 November 2016 as part of an ongoing partnership between the London museum and Berlin’s Deutsche Bank Kunsthalle, where it will travel to next. Launched in 2014, the collaboration aims to bring art from Africa, Asia and the Middle East to new audiences internationally. Fittingly named after a work believed to be a self-portrait, You Can’t Please All, acquired by the Tate Modern in 1996, the exhibition is an ironic reminder of the murky goodness that was Khakhar and of what informed his self-taught practice.

Bhupen Khakhar (1934-2003) is described as one of India’s pioneering Modernist painters who brazenly championed the bazaar aesthetic, combining Indian traditional art with Western pop art. His oeuvre can be traced to 1962, when he moved from Bombay to Baroda and joined the Faculty of Fine Arts at Maharaja Sayajirao University for a Masters degree in Art Criticism. Mentor and friend Ghulam Mohammed Sheikh introduced him to a network of artists, intellectuals and poets, each of whom would contribute to their co-founded journal Vrishchik (or Scorpion, 1969) and become regulars at the numerous parties Khakhar hosted.

Khakhar was to become a bohemian personality who surrounded himself with people, each of whom he learnt from and who in turn, sheltered his deep complexes. You Can’t Please All (1981) is considered iconic because it signalled Khakhar’s self-awareness as a gay man and suggests the personal difficulties he faced at the time. The painting depicts a nude lifesize figure on a balcony watching characters from an ancient Aesop fable.

The retrospective unfolds chronologically and includes oil paintings, watercolours, experimental ceramics, accordion styled books and a biographical diary. Comprising works executed over five decades, one can trace the many artists and artistic styles that inspired Khakhar’s own work. In the 1960s, it was the Company School and the art of Raja Ravi Varma. In the 1970s, he drew from devotional and calendar art, inspired in particular by Kalighat and Nathdwara paintings as well as the awkwardly flat 14th century Sienese frescoes. This was also the time he began making his “trade paintings” – a series of 1-square-metre sized portraits of people defined by their occupations. Amongst them are De-Lux Tailors (1972) and Barber’s Shop (1973) – narratives of ordinary lives, of the city’s petty bourgeois that represented India’s urban reality.

Following the work of American modernist painters like Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg, Khakhar experimented with collage in paintings like the Pan Shop (1965) and Night (1996). His lack of formal training allowed him to freely borrow from Western artists like Henri Rousseau, Howard Hodgkin and David Hockney. It was the way Hockney and others in Britain represented homosexual subjects that drew Khakhar to explore a more ‘truthful’ art, eventually evolving into an autobiographical practice.

The boundaries that divided private and public, conservative and modern, bourgeois and elite played out on the same plane in Khakhar’s paintings. Diagnosed with prostate cancer in 1998, Khakhar re-focused his work on ‘disease’ – an invasion of the human body and the humiliation of bodily failure. Khakhar returned to the luminous Kalighat-inspired technique as their translucent glazes of colour enabled him to portray human fragility: the grotesque with the attractive, the worldly with the personal.

The exhibition is a timely reminder of the importance of non-Western artists in a global context, reiterated by the number of reviews and commentaries that the show has generated. Khakhar’s art allows visitors to enter his work through different vantage points, and to recognise Western artistic influences while expanding awareness to a parallel art history on the Indian sub-continent.