Gallery Threshold features solo exhibition of works combined with personal belongings from the life of V. Ramesh.

Indian artist V. Ramesh brings the details of everyday life into his paintings, prompting viewers to have a closer look not just at the art but at the world surrounding them.

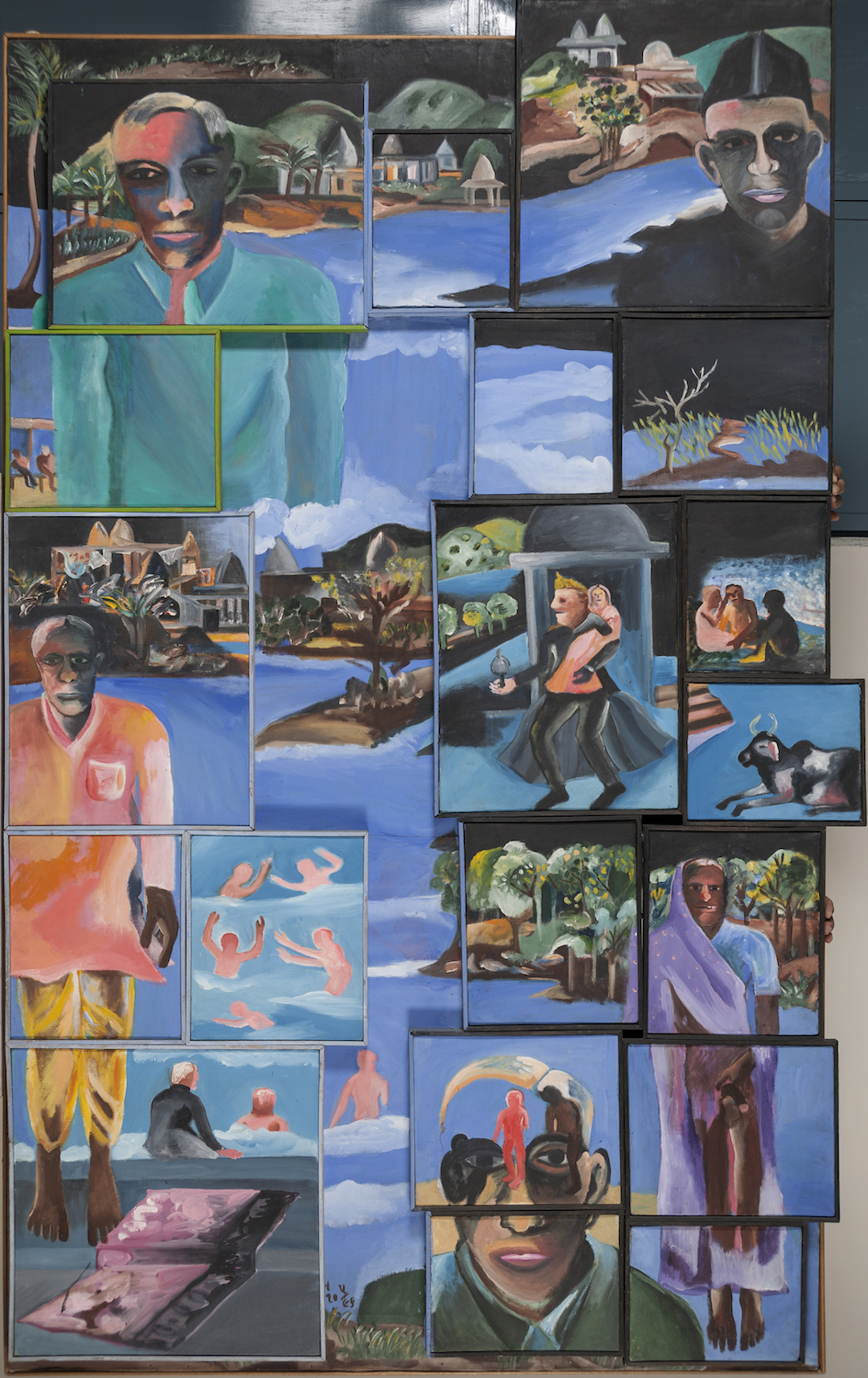

Art is more often than not, inseparable from the biography of its maker, and the art of Andhra-born and -based artist, V. Ramesh is no exception. For him though, the story of himself as painter is a more universal story of being human. The figurative form of his painted subjects allude to an outer body, an encasing that holds a deeper, truer form. It is no coincidence then that each of Ramesh’s narrative paintings is punctuated by a material ephemerality, visually discernable in multiple layers.

For his recent solo entitled “In my own words…” at Gallery Threshold in New Delhi, the artist presents more than his art. Akin to a theatre stage, the gallery is propped with the artist’s personal belongings. A reclining chair that also features in the painting on the wall behind it, a small studio table propped with books, a mirrored dresser, an umbrella and a calendar with a photograph of the greatly revered Indian sage, Sri Ramana Maharishi are also on display. Each object leads us to better understand the man behind the art.

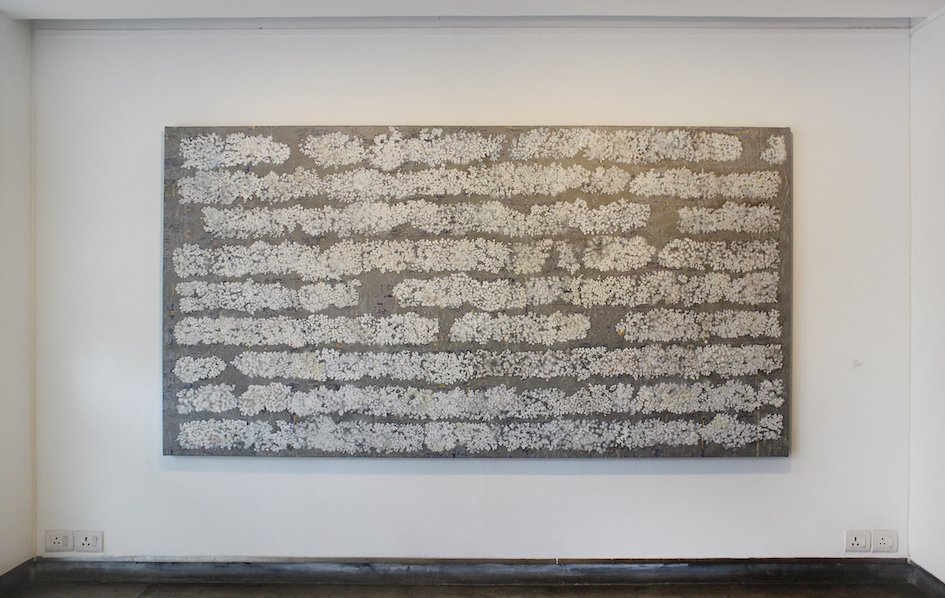

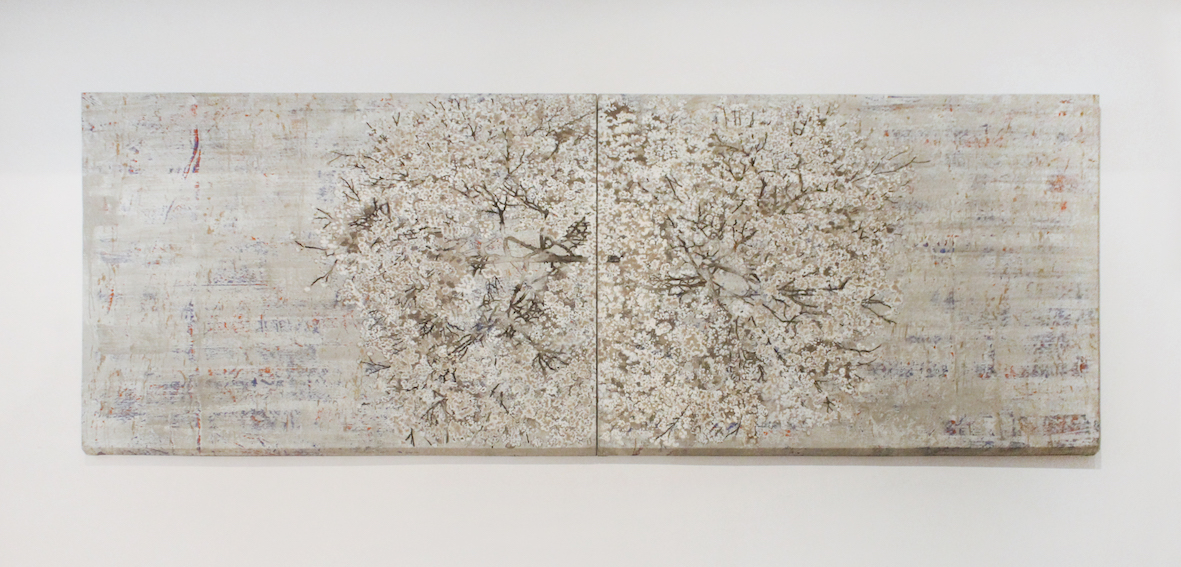

The exhibition features three distinct stylistic series and a large unfinished self-portrait of the artist reclining on his favourite chair. Begun over a decade ago, the 10-by-12-feet canvas became a backdrop in the studio for other paintings being worked on, gathering drips and smudges of paint as well as layers of dust. The image of a contemplative painter seated back in his chair, looking at the smeared surface of his canvas, makes for a rather ironic but somewhat perfect self-image. Alongside this are three narrative canvases, whose figuration is drawn from different scenes of the Indian epic The Ramayana. Describing feelings of wonder and fascination to having heard these stories narrated to him by his grandmother as a child, Ramesh paints them anew as an emotional landscape that riddles the observer into seeing a depth of visions.

The three allegorical paintings entitled Saavadhan, Genesis of an Epic and The Moment of Epiphany, all executed in 2016, are largely inspired by the medieval literature of mystical saints and bhakti poets. As Ramesh speaks with Art Radar, he shares his deep respect and lure to the lives of great women scholars like the Kannada poet Akka Mahadevi, and Lalleshwari of the esoteric Kashmir Shaivite tradition. As these poets’ words urge the devotee to look beyond the body and seek one’s true nature, so do the artist’s paintings by urging the viewer to look beyond its surface and recognise the essence of the story’s plot. Each painting is accompanied by a text and graphic illustration, giving the viewer context to read into the painted forms.

In the corridor that connects the two larger spaces of the gallery are hung a series of seven watercolours that each portrays a peacefully seated dog. Inspired by his many visits to the ashram of Sri Ramana Maharishi, the artist describes the dog as the ideal devotee. Against a faintly painted, distant landscape, like a tracing of the fragile world we occupy, the dogs lie faithfully in the foreground.

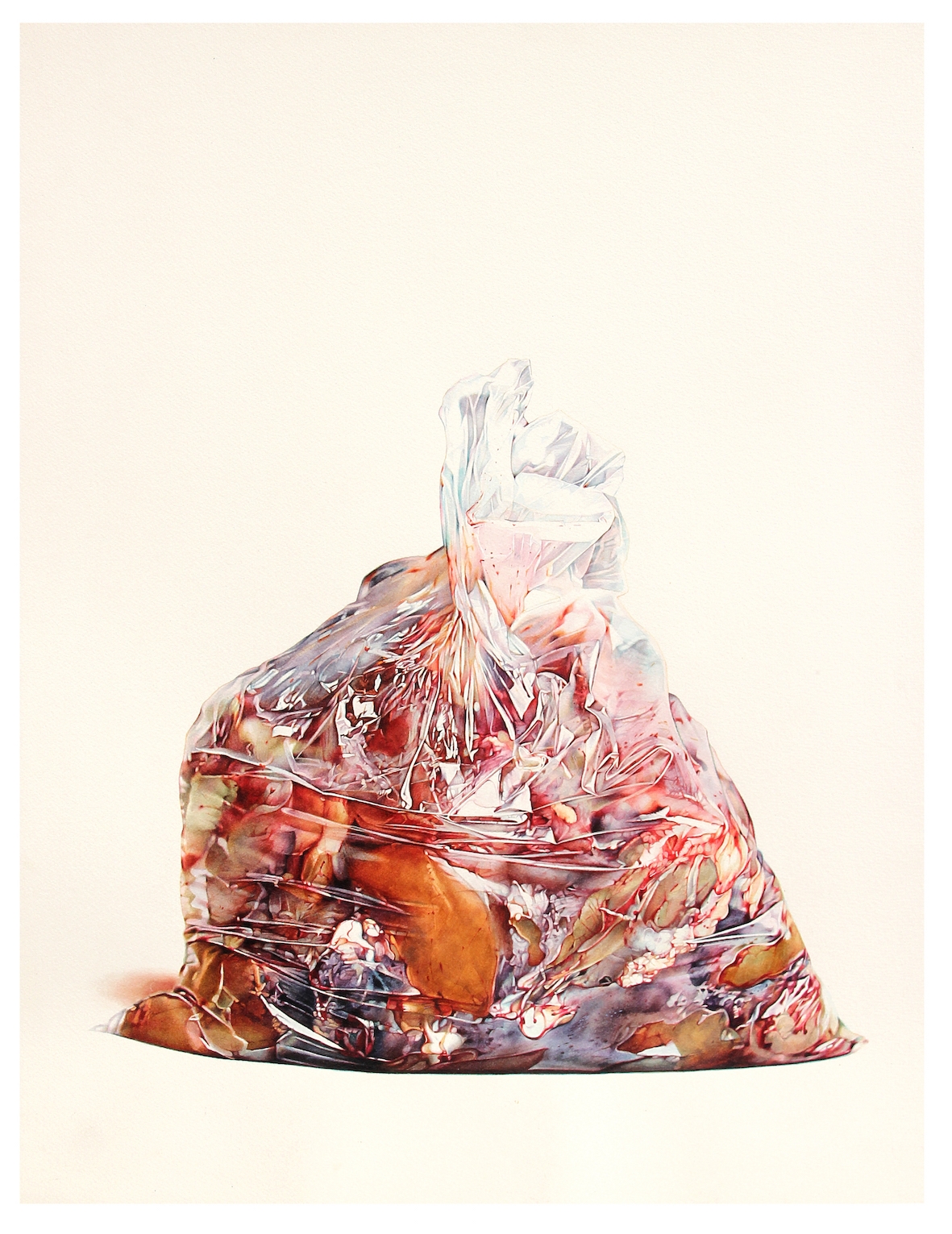

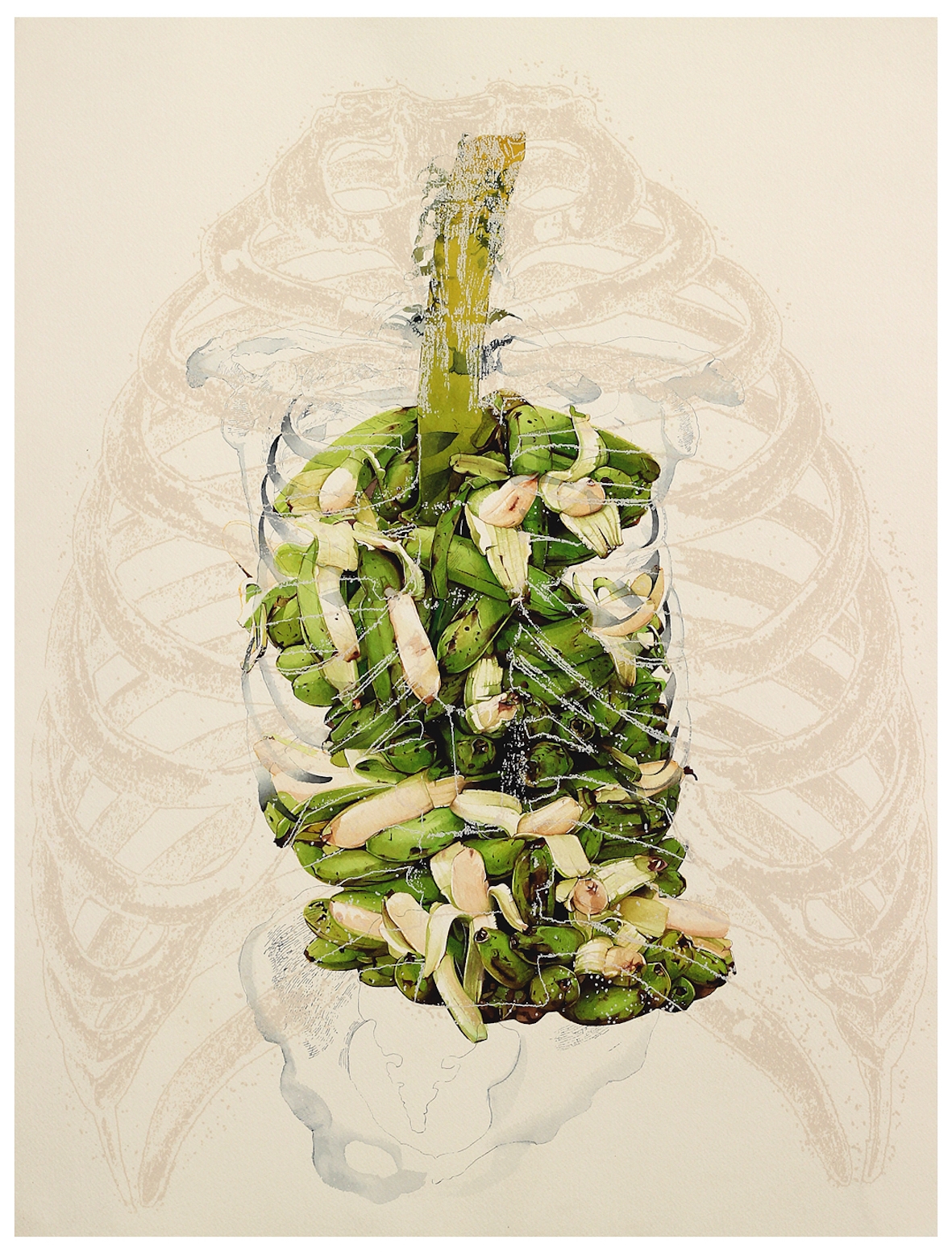

Ramesh’s desire to express gratitude to the knowledge he gained at the Ashram resulted in the ongoing series of 108 drawings – or offerings, as they are also titled. A bag of meat that he saw a man once carrying in a plastic bag for instance, is painted in hyper-realistic detail alongside the painting of a ripened pomegranate that has literally burst out of its skin. In another Offering, this time of a banana, the painter skillfully paints what appears to be a shadow of a human skeletal torso, the fruit playing the visual metaphor of embodiment of an innate self that when ripe sheds its bodily manifestation.

The exhibition reveals the artist’s mastery in painting his subjects, for each is a manifestation of his own memories and observations. Standing closer and then moving farther back to view each painting, the viewer’s eye is constantly challenged to look deeper. Steeped in ideas of devotion and faith, the V. Ramesh’s ability to so lucidly translate his thoughts onto canvas is admirable and does leave the viewer questioning the surface of the things he sees, and of the world he sees.