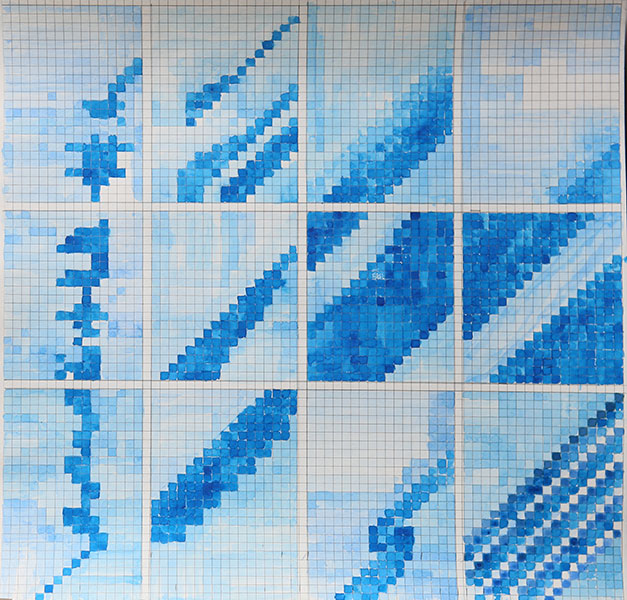

From the series Patterns of a Tactile Score, Watercolour on paper, 18.5” x 18.5”, 2017 – 2018

Yasmin Jahan Nupur’s art practice is influenced by the socio-political developments that have shaped the ecological and cultural landscape of Bangladesh, and helped define the values of the community at large. Her work is socially engaged, and to that extent, is emotionally charged. For her solo, she presents works on paper, in thread and in net, alongside two neon sculptures.

Patterns of a tactile score is an iteration of the artist’s process-based research in the fine weaving technique of Jamdani. Comprising delicately woven textile forms, and drawings inspired by the weaver’s array of floral and geometric motifs, the show reflects the artist’s interest in pliable sculptural forms, and explores the dialectic of tension as language.

Yasmin’s leaning toward experimenting with textiles dates to memories of her fascination with her mother embroidering, observed as a young child. Her first foray into making textile art dates to 2008, when her interests in history, community and material coincided in the craft of Jamdaniweaving. Originating in Dhaka, and celebrated as one of the finest muslins ever produced, patronized by royalty and traded to various parts of the world, the now almost lost weaving technique finds a voice in Yasmin’s art.

In weaving, the basic structure of the woven material relies on a grid to materialize[i]. With threads intersecting at right angles, a system or matrix of grids is built to form a piece of cloth. This matrix resolves the physical and aesthetic in its form, corresponding respectively to material and ideology, and functioning at once as structure and as symbol. In Yasmin’s sculptures, the matrix extends beyond the surface of the material to suggest the communal network of weavers that labours to produce it. Focused on the process, tactility and structural arrangement, the textile sculptures are rescued from the definition of object, emphasizing instead an order antithetical to that of natural objects.

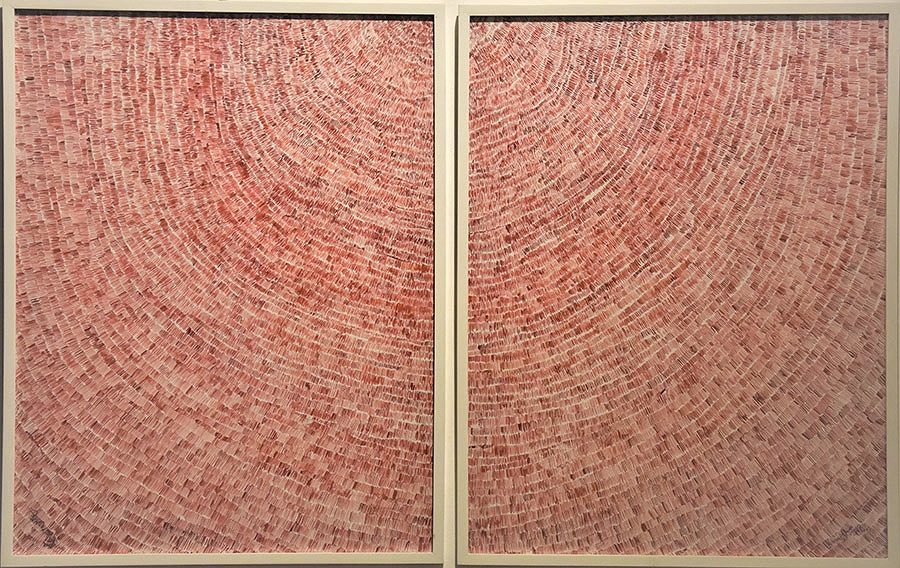

Accomplice to the sculptures is Nupur’s series of geometric drawings that again, underline the significance of the grid. Painted in the manner of graph paper, an aid used by weavers to guide design, the logic of the network of squares is more clearly manifest. The 25 drawings deliberately displayed as a grid, together form lyrical patterns that read like a musical score.

In her book On Weaving, 1965 the artist and weaver, Anni Albers dedicates a chapter to ‘Tactile Sensibility’ in which she elaborates on the surface qualities of materials and the human need to touch the things we form, a way of assuring ourselves of reality. She writes, “Sometimes material surface together with material structure are the main components of a work; in textile works, for instance, specifically in weavings or, on another scale, in works of architecture”.

As a living tradition, jamdani weaving presents ‘cultural threads’ that carry the memories of the people and their land. As a socially dynamic material, it is a signifier of civic identity. While the sculptural work embodies the labour of the weavers and the endurance of their craft, unchanged since the time of its birth, the artist’s hand asserts the work’s refusal to be viewed simply as fine fabric or as rigid sculpture. The work serves, as a form of quiet resistance and in doing so, is both a displayed act and an exhibited sculpture[ii].

Intrinsic to the history of textiles is the history of women and the feminist agenda for equality within a male dominated historical narrative. Subversively employed by feminists in the 1960s and 70s, fiber arts were a means by which women addressed issues of identity, social place and sexuality. With its obvious links to domesticity, textiles came to be asserted as a tool to interrogate ‘women’s work’, challenging stereotypes and reclaiming a position within ‘high art’. The gendered architecture of the medium underpin Yasmin’s art in a more subtle way, where it follows the schematic of the hand-made rather than of feminist politics.

Stringing all the work together is the play of tension, both seen and implied. The work exists as a spatial interface, where it is delicately balanced in a state of constant suspension. Shaped by gravity, the sculptures remain in limbo- tethered to the ceiling and yet softly pulled to the ground. Observed on the loom where stretched threads are interlaced to form cloth, and activated through placement in the white cube, tensile energy is inherent to the work’s makeup as well as its representation and reading. Symptomatic of anti-form sculptures, the works made of gold and silver net float between form and formlessness, fleshing out the richness of the material while affirming a simple ‘flow’ of form that disorients and mesmerizes. The knots in each work lend strength to an otherwise fragile looking piece of mesh. Their shape is mutable, defined by the manner in which they are hung. The arching loops and dense clusters resemble a web- of linkages, of disruptions, of harmonies and rhythms.

At yet another level, threads are understood as episodes of life, occurring repeatedly, often in sequence. Borrowed from the logic of minimalism where multiple units repeat themselves to form the whole, embroidered sculptures like Manifesto, 2017 reveal an underbelly, where loose threads appear behind the embroidered metallic surface. This work makes the idea of the threshold lucid for the sheerness of the fabric is obstructed by silver yearn embroidery in a seemingly decorative way, punctuating our experience of the work.

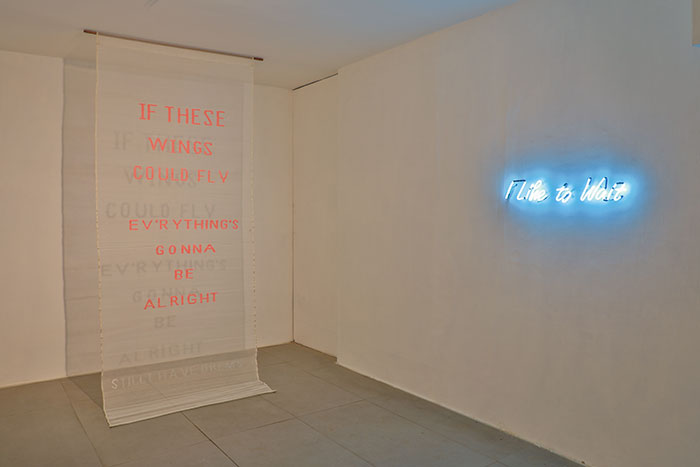

Yasmin’s body of work can be viewed as being in a ‘state of becoming’, where the personal narrative feeds into collective memory, most pronounced in works like Nobody Bought Anybody’s Silence, 2017 and Lucid Blue Dream, 2015. Here she offers a revision of political sight. While the shape of the sculptures themselves is more defined, the inclusion of text renders the structure of communication problematic. Crafted from the imagination of people for over two centuries, jamdani represents the temporal texture of its region, hinged on traditional processes, articulating the need to relocate our cultural inheritance.

Owing to its disposition as tactile material, textile elicits a sense of intimacy. Its associations with the feminine and its function as clothing frame the nature of our experience. Yasmin's insertion of text within the weave of her textile sculptures creates a situation where the viewer is faced with the dilemma of ‘correct understanding’. Urging the viewer to perceive each work of art beyond the framework of his or her own social prejudices, Yasmin’s neon work I like to wait, 2018 presents the contradictions of objective viewing in a ‘new light’. Teasing the viewer with a mysterious signage, she effectively unwraps the gulf between communication and understanding.

Drawing on Austrian philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein’s suggestion that language stems from a variety of social practices that control and make possible various forms of discourse, that he refers to as language games, Yasmin’s treatment of text can be seen as an ethnographic reading relating to the craft of textile making, its importance as a vehicle of social history and its contemporary applications and functions. Language therefore, is a social construct that represents an observable pattern or a series of codes whose rules change as per its usage in time and space.

Patterns of a Tactile Scoreis a parallel play on tensile and often emotive structural forms and on the textured fabric of place and people. The show activates the friction between art and craft and between language and experience.

References:

Albers Anni,On Weaving, 1974

Krauss Rosalind, Grids, 1979,reprinted in The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths

Morris Robert,Continuous Project Altered Daily, The Writings of Robert Morris, 1994

Whitney Syniva, The Grid, Weaving, Body and Mind, Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings, 2010